1. Academic Buildings

The McCosh Presidentcy: A "Bricks and Mortar" President

In his later years, after he retired as president of the College of New Jersey, James McCosh would boast to visitors, "It's me college. I made it."

He was not far off the mark. Although the College of New Jersey had been in existence for more than century when McCosh took office in 1868, it was then an institution adrift, still struggling to overcome the trauma of the Civil War. Enrollment remained low, the physical infrastructure was dated, and money was scarce.

By the time McCosh stepped down two decades later, the college had emerged as one of the elite institutions in American higher education. During his eventful tenure, the enrollment tripled to more than 600; the size of the faculty rose from 16 to 40; and the curriculum had been dramatically expanded and improved. McCosh stabilized the college's financial affairs by finding wealthy patrons to support his ambitious plans. And he inspired a generation of students, some of whom would emerge as key figures in Princeton's history --Moses Taylor Pyne, Class of 1877, Woodrow Wilson, Class of 1879, and Andrew Fleming West, Class of 1874, among them.

But perhaps McCosh left his most lasting mark on the campus itself. With McCosh as Princeton's first true bricks-and-mortar president, the college grew by 14 buildings during his 20-year tenure.

Princeton University. Property of the Trustees of Princeton University.

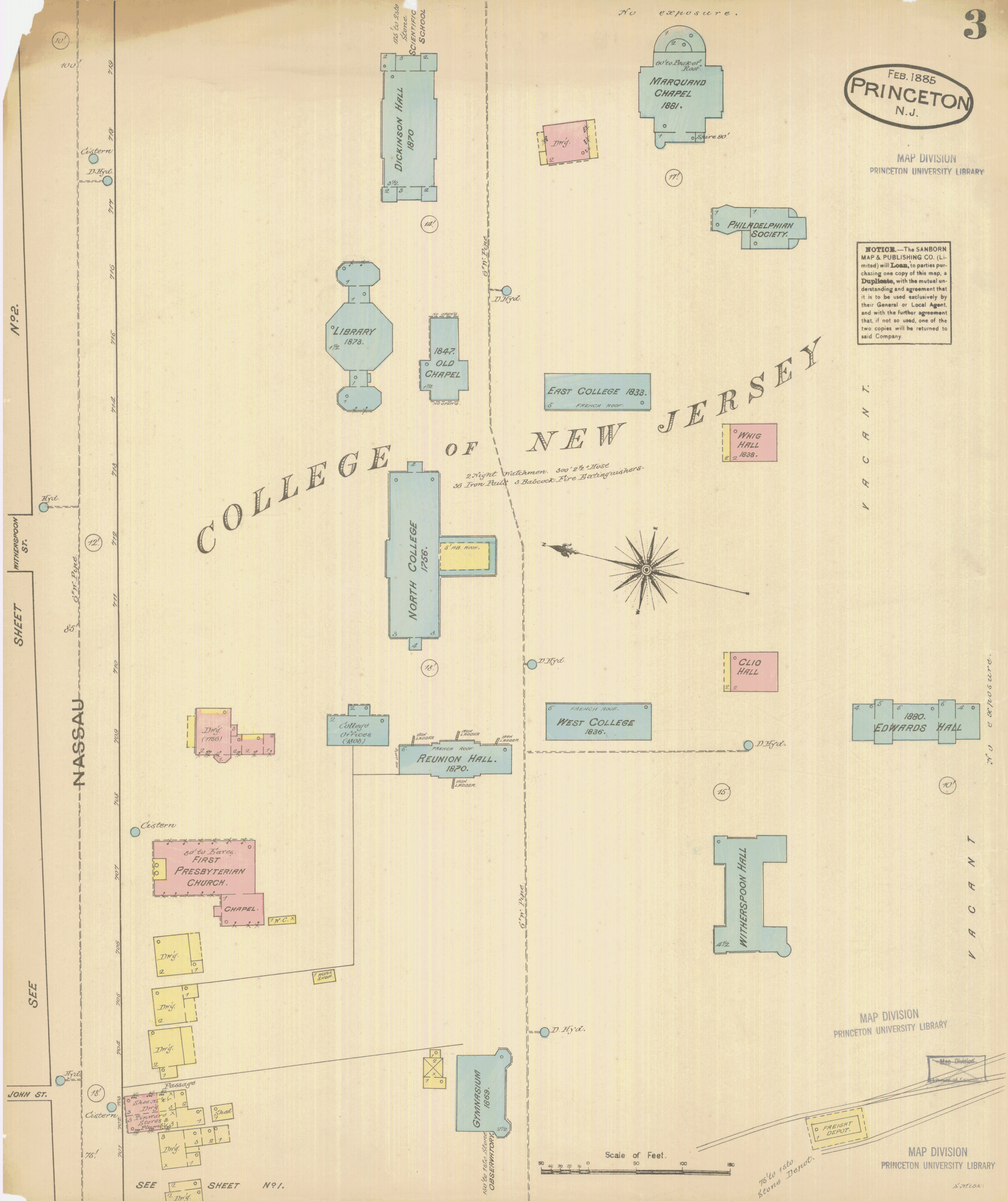

Sanborn Map Company Fire Insurance Map of campus, dated 1885, with stamp of the Library of Congress

Source: Princeton University Library

Dickinson Hall

Princeton University. Property of the Trustees of Princeton University.

Source: Princeton University Archives, Mudd Library, Grounds & Buildings, Box 31

In 1868, the year that James McCosh arrived in Princeton, the College of New Jersey was trying to complete its first new academic facility in almost 70 years. Initiated during the administration of John Maclean, Halsted Observatory was still under construction when McCosh took office and was the first of more than a dozen buildings he would dedicate as president.

Other than the new observatory, the College's academic facilities were sparse. The College library, then located in the south wing of Nassau Hall, was open only on a limited schedule and the collection itself was small and antiquated. Most classes were held in the cramped old recitation rooms of Nassau Hall, Geological Hall, and Philosophical Hall. Other classes met in professors' homes.

McCosh's first order of business was to construct a new classroom building. Dickinson Hall, constructed in 1869, and opened the following year, filled this pressing need. Designed by George B. Post of New York, Dickinson was notable in two respects: it foreshadowed the move toward the High Victorian Gothic style as the dominant architectural style on the campus, and it was the first major gift of John C. Green, the philanthropist who underwrote so many of McCosh's building projects.

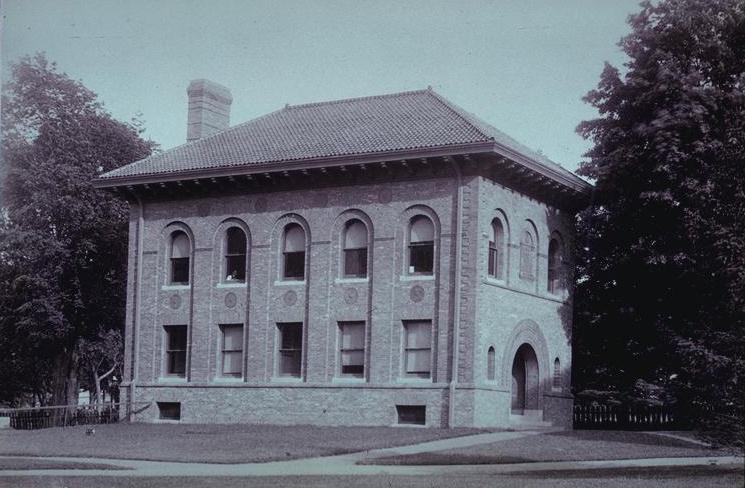

Chancellor Green Library viewed from the north (photo 1870's)

Other license.

Second on McCosh's list of academic priorities was a new library. In 1871, the College commissioned a 29-year-old architect named William A. Potter to design Chancellor Green Library.

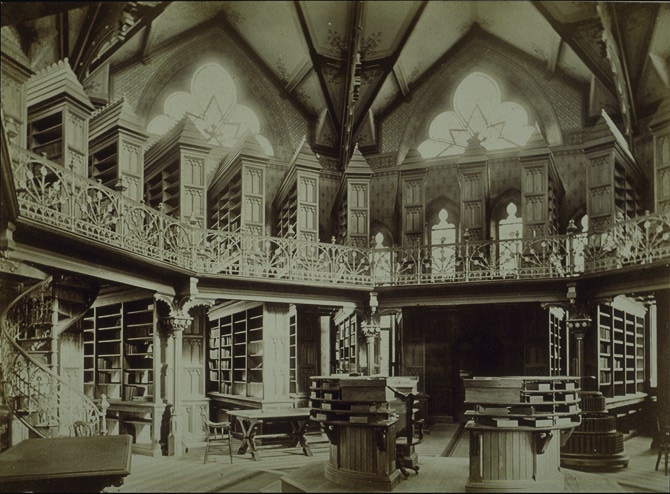

Interior, rotunda at ground level (photo circa 1874)

Princeton University. Property of the Trustees of Princeton University.

Source: Princeton University Archives, Mudd Library, Grounds & Buildings, Box 19

Donated by John C. Green and named for his brother, Henry Woodhull Green (a Princeton alumnus and Chancellor of the state of New Jersey), the library was an elegant octagonal structure featuring a striking central rotunda --then the most lavish building constructed to date on the campus. Chancellor Green Library was located to the immediate east of Nassau Hall and faced Nassau Street. Both its prominent placement and the high costs of its design and construction reflect the library's importance in McCosh's scheme for the College's institutional development.

Princeton's first purpose-built library was converted to other uses in 1946. When the High Victorian Gothic style fell out of favor, trees were planted to screen it from Nassau Street. (Later, the Joseph Henry House was moved in front of it, almost completely blocking it from public view.) Even so, it remains one of the real architectural gems on the campus. And perhaps most significant, the success of Chancellor Green Library marked the beginning of a three-decade partnership between Potter and Princeton that eventually produced Witherspoon Hall, Alexander Hall, and Pyne Library.

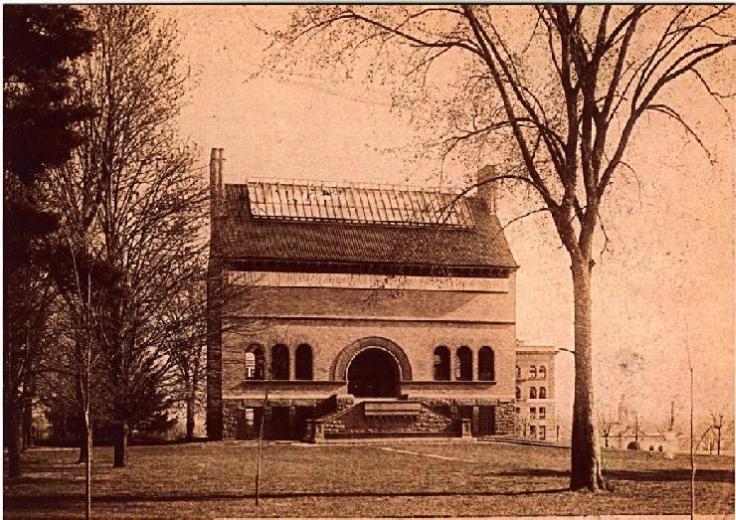

John C. Green School of Science, viewed from the west with Dickinson Hall at right (photo circa 1876-80)

Princeton University. Property of the Trustees of Princeton University.

Source: Princeton University Archives, Mudd Library, Grounds & Buildings, Box 63

With the library underway, McCosh turned to the urgent task of upgrading the College's scientific laboratories and equipment. Since the departure of Joseph Henry in 1848, the College had not modernized its facilities or kept pace with the new advances in fields such as biology, chemistry, and physics. Students studied these areas theoretically, but there was very little space in which they could perform experiments.

As McCosh put it, "lectures without experiments performed by the students may widen the mind, but they will not make chemists or give accurate scientific knowledge."

To address this issue, McCosh and John C. Green conceived of the John C. Green School of Science. Completed in 1874, this building contained lecture rooms, laboratories, and a museum, and it represented a tremendous step forward in the teaching of the sciences at Princeton. Not only did this facility give the College scientific facilities (and new equipment) on par with its peers, but the donor also endowed $250,000 for science professorships.

The School of Science was designed by Potter and was executed in the High Victorian Gothic style. Distinguished by a 140-foot-tall clock tower and the large arched window of the museum, it was prominently located across from the new library. The School of Science thus formed with Dickinson and Chancellor Green a quadrangle bounded by Nassau Street to the north.

Thus the focal point of the campus had shifted from the front and back campus of Nassau Hall to this new grouping of High Victorian Gothic structures and the enclosed lawn.

Class of 1877 Biological Laboratory viewed from the northwest

Princeton University. Property of the Trustees of Princeton University.

Source: Princeton University Archives, Mudd Library

With these three key buildings in place, McCosh turned to other priorities. More than a decade would pass before Princeton would commission another academic structure. Science again posed the most urgent need. By the late 1880s, the School of Science was bursting at the seams, and McCosh responded by encouraging the building of two more structures: the Class of 1877 Biological Laboratory, designed by A. Page Brown,

Chemical Laboratory, viewed from the northwest (photo circa 1893)

Princeton University. Property of the Trustees of Princeton University.

Source: Princeton University Archives, Mudd Library, Gronds & Buildings, Box 1

and the Chemical Laboratory, designed by Richard Morris Hunt.

Chemical Laboratory in Princeton Architectural Catalog

View of Dynamo Building in the 1920's, with Chapel in background

Princeton University. Property of the Trustees of Princeton University.

Source: Princeton University Archives, Mudd Library, Grounds & Buildings, Box 32

Although both of these buildings were completed after McCosh retired, they constitute part of his educational and architectural legacy. Along with the Dynamo Building, built to support Professor Cyrus Fogg Brackett's pioneering experiments in electrical engineering, these structures underscored McCosh's commitment to the sciences. McCosh was an early advocate of a balanced curriculum, and no student graduated from Princeton during his tenure without a solid grounding in the classics, mathematics, and the physical sciences.

Museum of Historic Art - 1890

Princeton University. Property of the Trustees of Princeton University.

Source: Mudd Archives, Pach Bros Photo

Indicative of McCosh's commitment to a well-rounded education was his enthusiastic support for one final academic building: an art museum to house the Department of Art and Archaeology. In 1882, an alumnus named William C. Prime promised to donate his famed collection of ceramics to the College -- provided that a suitable, fireproof building were built to house it. It took McCosh several years to mobilize the resources to construct such a building, but by 1887 he had commissioned a rising young architect named A. Page Brown to design the Museum of Historic Art. The Museum reflected both McCosh's interest in expanding the curriculum into new fields, including art, and also his desire to elevate the mind through the appreciation of beauty. Brown produced a solid Romanesque Revival building, scaled back from its initial plan but nonetheless appropriate for the size of the collection. The choice of the Romanesque style also cut down on costs; a polychromatic High Victorian Gothic building would have been far more expensive, as would a classically inspired structure made of marble.

Intended from the start as a teaching facility as well as a display space, the museum was located approximately on the site of the current Art Museum. With its neighbors Dod and Brown Halls, it helped form a cluster of Renaissance-influenced buildings on the east side of the campus.

By the time McCosh retired, the campus had been utterly transformed. The Colonial, Federal, and Greek Revival core of the campus, grouped around Nassau Hall, no longer commanded center stage. The new visual focal point of the College was the set of new buildings to the east of Nassau Hall, all designed in the popular High Victorian Gothic style. To the south and southwest of Cannon Green, meanwhile, stretched an irregular series of new dormitories and other facilities. Both the individual buildings and the campus as a while were characterized by an asymmetrical appearance that was sharply at odds the classical, symmetrical plan for the campus that had been sketched by Joseph Henry a half-century before.

But McCosh did not believe in building simply for the sake of building. "Some critics found fault with me for laying out too much money on stone and lime; but I proceeded on system, and knew what I was doing," he wrote in his farewell address. "I viewed edifices as a means to an end."

Foremost among the ends that McCosh had in mind was to elevate the College of New Jersey to national prominence. When he assumed his new post, he identified three broad areas in which the College had to improve. First, Princeton needed modern academic facilities, particularly for the sciences. Second, something had to be done to help the student body, whose living conditions bordered on the primitive. Third, the College's religious and spiritual roots required tending.

McCosh's building program addressed each of these areas. For the students, he built a magnificent new gym and new dormitories for students, both rich and poor. On the academic front, he erected an elegant new library, a building dedicated to the teaching of the physical sciences, and other classroom and laboratory buildings. And as a staunch Presbyterian, he built an impressive new chapel and supported an evangelical resurgence on the campus.

Today, however, McCosh's architectural legacy is not immediately apparent. Many of the McCosh-era structures burned down or have been destroyed, and the surviving buildings appear somewhat out of place on the now predominantly Collegiate Gothic Princeton campus. Consequently, buildings such as Witherspoon Hall are often unfairly maligned as "Victorian monstrosities."

When we look back on the campus of the 19th century, however, we realize that McCosh oversaw a particularly vibrant period in the College's architectural history. At least two of the buildings he commissioned -- Chancellor Green Library and Marquand Chapel --are exquisite works and among the finest ever built at Princeton. McCosh also enlisted several talented architects of the period to help him realize his dreams, including A. Page Brown, William Appleton Potter, and Richard Morris Hunt.

The High Victorian Gothic and Romanesque Revival styles employed by these architects may not please modern tastes, but that does not diminish the quality of those buildings. Instead, the McCosh-era buildings must be viewed as expressions of contemporary fashion and of the College's increasingly self-confident view of itself.

In this regard, McCosh's most significant contribution to Princeton's architectural evolution was the example he set. He demonstrated that the College could mobilize resources to expand its facilities and thus improve its scholarship and prestige. McCosh had discovered a fundraising principle that still holds true today: donors like investing in bricks and mortar. McCosh's ability to cultivate a new group of affluent donors assured Princeton's financial future and laid the groundwork for later growth.

On arriving in Princeton in 1868, McCosh had told the assembled crowd that the purpose of a college education was to "elevate and refine the mind." The College he inherited had precious few facilities to achieve this noble purpose. But by inspiring others (notably John C. Green) to adopt his vision of Princeton as a great national university, McCosh was able to change all that. The academic facilities he built served the College with distinction for a half-century or longer. Ultimately, this contribution matters far more than their relative architectural merits.