2. The First Structures

Jonathan Belcher

Princeton University. Property of the Trustees of Princeton University.

His Excellency Jonathan Belcher, Esq., 1734. Mezzotint by John Faber (died 1756) after a painting by Richard Phillips (1681-1741). Gift of Samuel S. Dennis and Charles W. McAlpin, Class of 1888. Courtesy of Graphics Arts Collection, Princeton University Library

William III

Princeton University. Property of the Trustees of Princeton University.

Portrait of William, aged 27, in the manner of Willem Wissing after a prototype by Peter Lely

Happily for future generations of Princetonians, he declined this offer. Instead, Belcher urged that the new edifice be named Nassau Hall after King William III of the House of Nassau, widely known as William of Orange.

Nassau Hall and President's House

Princeton University. Property of the Trustees of Princeton University.

When the Trustees met again in May of 1756, they quickly adopted Nassau Hall as the official name for the building and agreed to open the College in Princeton that fall. Nassau Hall would be several more years in the making. In July 1754, the Trustees had authorized a Building Committee to erect "the College, a President's house, and a kitchen...as soon as they think necessary." The original plans for all three structures were drawn up by a master carpenter from Philadelphia named Robert Smith , with the assistance of Dr. William Shippen Sr., the brother of a college Trustee. A local mason, William Worth, supervised the actual construction.

Facade of Nassau Hall

Princeton University. Property of the Trustees of Princeton University.

Together, they devised the plans for a structure that measured 177 feet long and 53 feet wide -- enormous for the time. Its plain sandstone walls were 26 inches thick and penetrated by dozens of tall, narrow windows.

Ground was broken for the new building on July 24, 1754, and the cornerstone -- the northwest corner -- was laid in September of the same year. By November 1755, Nassau Hall's hipped roof was raised and by the following spring the building was nearing completion.

The building rose three full stories, plus the half-basement. This half-basement not only allowed some natural light to penetrate the dank recesses of the basement, but also had the practical effect of helping keep it from flooding constantly. Central New Jersey has a high water table, and the basement rooms of Nassau Hall were perennially damp.

Smith's scheme for Nassau Hall drew on a number of antecedents. Princeton historians have tried, without great success, to find Smith's models, which he would have known through architectural pattern books. In the view of the Princeton historian T.J. Wertenbaker, for instance, Nassau Hall resembles an unornamented version of King's College, Cambridge. According to legend, Smith owned a copy of a popular building primer of the time, Gibbs's A Book of Architecture, which included a reproduction of King's College. The cupola, Wertenbaker says, is a copy of St. Mary-le-Strand, also shown in Gibbs; the main doorway was borrowed from Batty Langley's A Builder's Treasury of Designs.

What is uncontestable is that Smith brought his architectural knowledge to bear on the problem of erecting an impressive, functional, and appropriately inexpensive structure to house the College. By these standards, he succeeded and created a building worthy to stand with its peers.

Structurally, Smith's Nassau Hall is a sturdy "double pile," having two blocks extending from a central pavilion. Three doors opened onto the front lawn facing the King's Highway, and two onto the back. The Trustees originally specified that the structure be built of brick -- but only if good brick could be made cheaply and easily in Princeton. Apparently this could not be done, or perhaps local sandstone was cheaper, because the building was executed in stone.

In any event, the rough, simple sandstone of Nassau Hall was well suited to the chaste sensibilities of the College. Certainly President Aaron Burr, Sr. was not exaggerating when he wrote to a donor in Scotland, "We do everything in the plainest and cheapest manner, as far as is consistent with Decency and Convenience, having no superfluous Ornaments."

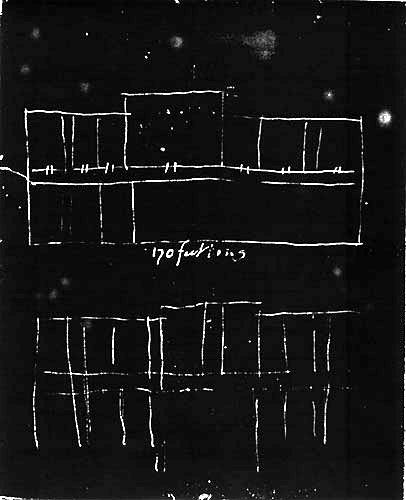

Foundation Sketch

Princeton University. Property of the Trustees of Princeton University.

Smith designed Nassau Hall to provide space for all the functions of the College: it included a dormitory, chapel, dining hall, library, and recitation rooms. According to a rough sketch of the foundations made in 1754 by Ezra Stiles , then president of Yale, the central pavilion housed the classrooms and library. On the southern portion of the pavilion, the prayer hall protruded slightly. The two side blocks held dormitory rooms. The basement was devoted to the refectory and more bedchambers.

With three students to a bedchamber, and with some of the less fortunate students consigned to the damp and poorly lit half-basement, the building could house about 150 people -- far more than were enrolled at the time.

Nassau Hall had twelve chimneys -- a necessity of life in the days before central heating. In 1762, a simple frame kitchen, managed by a steward, was attached to the rear of Nassau Hall, probably through a wooden passageway. There were also the inevitable back buildings: privies. Nassau Hall did not receive indoor plumbing for another century.

This, then, was the building into which the College of New Jersey moved in the fall of 1756. Students and tutors alike took up residence in the new dormitory rooms.

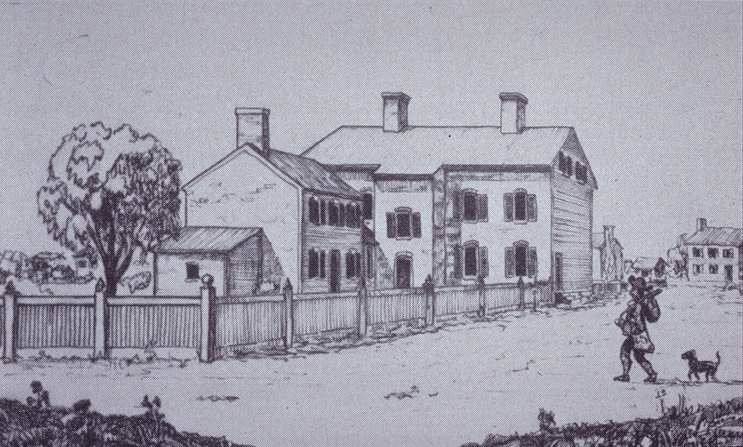

President's House

Princeton University. Property of the Trustees of Princeton University.

While the students and tutors occupied Nassau Hall, President Aaron Burr and his family moved into the other college building, the President's House. This building, still in its original location, is now called Maclean House. It served as the President's residence until 1878.

The President's House, built for around 600 pounds, gave Robert Smith the opportunity to design a companion structure on a much smaller scale. The result provides proof of Smith's ability to address varied architectural programs. Its simple but handsome lines and elegant proportions suitably contrast with the looming bulk of Nassau Hall. It has a brick core and wooden bays that were added in anticipation of President James McCosh's residency in 1868.

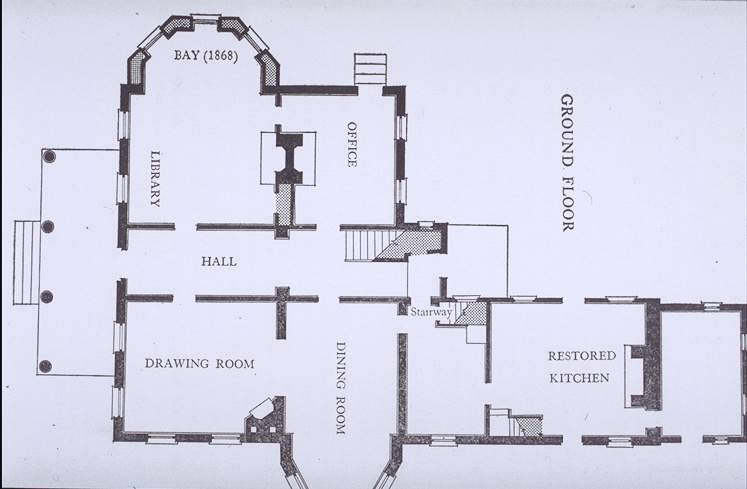

Floor Plan

Princeton University. Property of the Trustees of Princeton University.

Smith designed the house to harmonize with Nassau Hall in its symmetry and original buff color. The one-story kitchen at the rear of the house was originally a separate building, but it is maintained that in the first of many renovations to this structure, President Burr had a passageway constructed that would enable his slave, Caesar (bought in 1755 for 80 pounds), to bear hot food from the big cooking fireplace in the kitchen to the dining room inside the house. The kitchen was also placed so that it could serve the residents of Nassau Hall in need.

Burr lived in the house for only a year. He died in 1757 at the age of 41, with his widow, Esther, living only a year longer before dying from smallpox. They left two young children, including a two-year-old boy named Aaron Jr.

After Burr's death, the College struggled through a rapid succession of presidents. The third president, Jonathan Edwards , died after only a year in office; it was in the President's House that he received the smallpox inoculation that killed him. He was succeeded by Samuel Davies , who served from 1759 to 1761. The fifth president, Samuel Finley, was at Princeton only a few years before passing away in 1766. Finley left the most notable mark on the house, reputedly planting the two large sycamore trees that still stand in front. These are the so-called "Stamp Act" trees, marking the year they were planted.

After 1878 the building served as the Dean's House (and was known by this name) until 1968, when it was renamed in honor of Princeton's 10th president and turned over to administrative uses. The house has since been designated a National Historic Landmark.

Anecdotes and legends of President's House may be found here

Only the modesty of a Harvard-educated colonial governor kept Princeton from naming its original building Belcher Hall. The Trustees wanted to name the structure after the College's most important benefactor, Governor Jonathan Belcher .