Traditionalism and Budgets

By the time Goheen took office, Princeton was coming to the end of a prolonged period of fiscal austerity that dated to the Great Depression. In the quarter-century starting in 1933, the University built only four new buildings. With money tight, Harold Dodds had focused on upgrading academic programs; this had the effect of creating a great latent demand for new academic facilities, especially in the sciences. Enrollment had risen by 650 as well, putting severe pressure on Princeton's aging dormitories and threatening the ideal of the "residential University" so cherished by Presidents Hibben and Dodds.

But by the mid-1950s Princeton could again afford to contemplate an ambitious construction program. America's increasing post-war affluence meant that the University could again set -- and achieve -- lofty fundraising goals. The $53 million "University Campaign" of 1959 created the funds for campus expansion.

This campaign completed a planning process that began in earnest in 1954, when Douglas Orr was appointed Supervising Architect of the University. Assuming the funds could be raised to pay for new construction, Orr and the Princeton administration faced two major challenges: where to locate all the new buildings that were needed, and what architectural style in which to build them.

As envisioned in a long-range master plan from this period; the siting problem was the easier of the two to solve. The campus would expand to the south, encroaching on the athletic fields and tennis courts that lay below Patton, Walker, Guyot, and Eno Halls. It would also grow to the east, along William Street. And selective additions would be made in the core of the main campus, particularly in the large open space between Prospect House and 1879 Hall.

Deciding on an appropriate architectural style proved more problematic. In 1956, the Princeton Alumni Weekly ran a long feature entitled "After Gothic, What?" that included photographs and descriptions of some of the modern buildings then under construction at Harvard, Yale, and MIT. Unlike Princeton, which had since 1896 endeavored to have all of its buildings harmonize in a similar style, Harvard and Yale were erecting structures that boldly contrasted with their neighbors. With the traditional Collegiate Gothic style of the campus no longer practical, Princeton faced a difficult decision about what style would replace it.

Princeton University. Property of the Trustees of Princeton University.

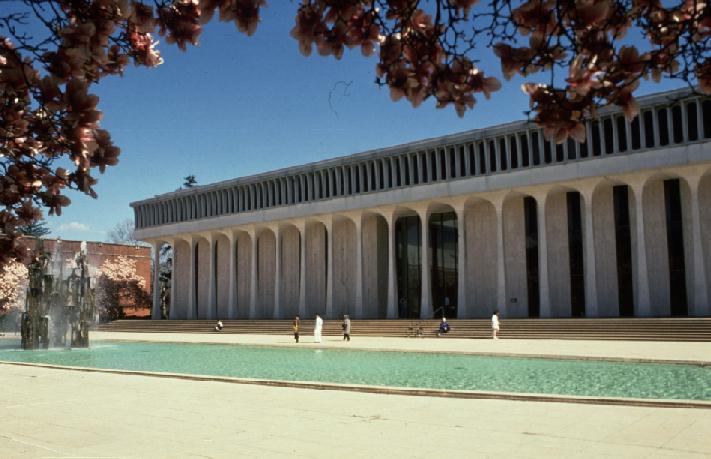

In the end, the University finessed this decision. With a few notable exceptions, such as the Minoru Yamasaki's bright white Woodrow Wilson School building, during the 1960s Princeton commissioned an uninspiring series of functional modern structures built of various shades of brick. The new buildings were conventional, cautious, and designed to complement rather than compete with their Collegiate Gothic neighbors.

The position of the trustees who mandated this conservative approach to campus expansion is understandable. By the late 1950s, after all, the campus had not changed materially in 30 years, and to most members of the board, the identity of Princeton was indelibly linked to the unchanging gothic campus of Wilson and Hibben. In their view, to experiment with new styles would undermine the architectural cohesion that had been at the center of the University's physical planning since the days of Ralph Adams Cram.

The stubborn traditionalism of the trustees ran directly into unpleasant modern realities of cost and materials. For one, the distinctive local stone used in the old Collegiate Gothic buildings was in short supply, even if skilled masons could have been found to use it. Moreover, in the post-war world there was no way that a private institution such as Princeton could afford the kind of craftsmanship and labor that had gone into the older buildings. The sheer scale of the contemplated expansion also argued for the choice of inexpensive materials and simple designs.