2. Geological and Philosophical Halls

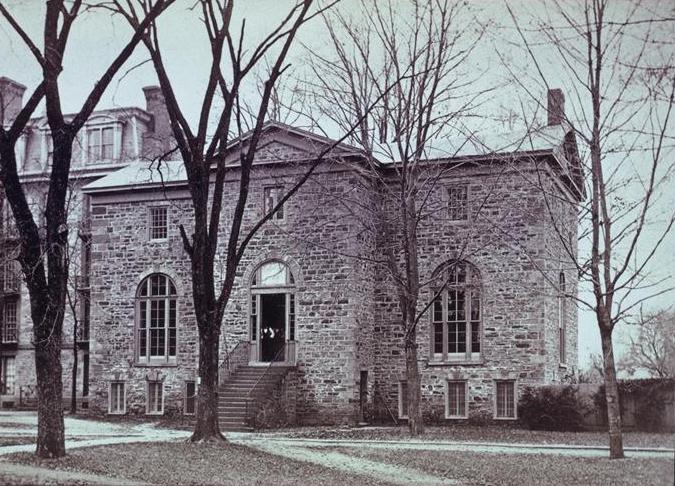

Geological Hall viewed from the east (photo after 1871)

Princeton University. Property of the Trustees of Princeton University.

Source: Princeton University Archives, Mudd Library

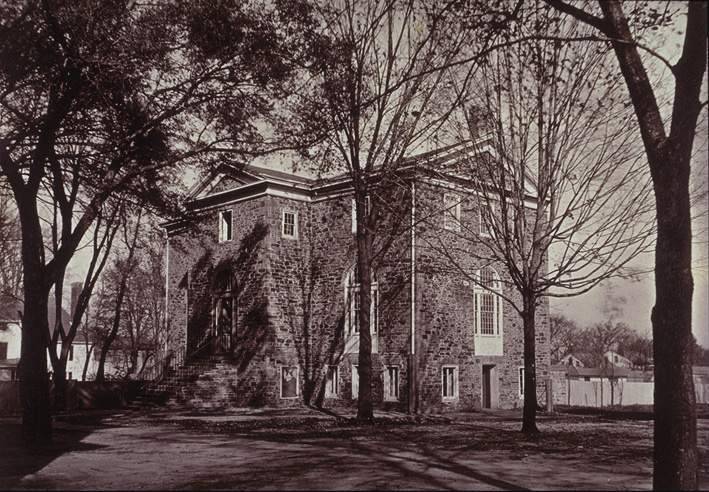

Philosophic Hall viewed from the southwest (photo c.1870)

Princeton University. Property of the Trustees of Princeton University.

Source: Princeton University Archives, Mudd Library, Grounds & Buildings, Box 59

The Trustees officially commissioned Geological and Philosophical Halls on 13 April 1803, specifying that the buildings should be "60 feet in length and 40 feet in breadth and three stories high."

Philosophical Hall was designed to serve several purposes. It contained a room for the College's philosophical apparatus (as scientific instruments were then called), as well as classrooms for the teaching of chemistry and natural history. In addition, it was to accommodate a "Kitchen or Cooking room for the use of the Steward of the College," as well as "a large and convenient dining room for the students."

Geological Hall, meanwhile, was primarily designed to provide rooms for classes and studying. Latrobe was also instructed to provide "a room for the reception and handsome exhibition of the Library of the College." The College's two famous debating societies -- the American Whig Society and the Cliosophic Society -- were housed on the top floor of Geological Hall.

As such, Geological Hall soon became a focal point of campus life. In the early 19th century, professors as well as students belonged to Whig and Clio, and the two debating societies contributed considerably to maintaining the college's intellectual vitality.

Sandstone Masonry

Princeton University. Property of the Trustees of Princeton University.

Source: Unknown

Both buildings were executed in "Stockton sandstone" to match the walls of Nassau Hall. The masonry

work was somewhat more refined than that of Nassau Hall. Learning from their unpleasant experience with the cast-iron roof on Nassau Hall, the Trustees authorized slate roofs for the two new structures.

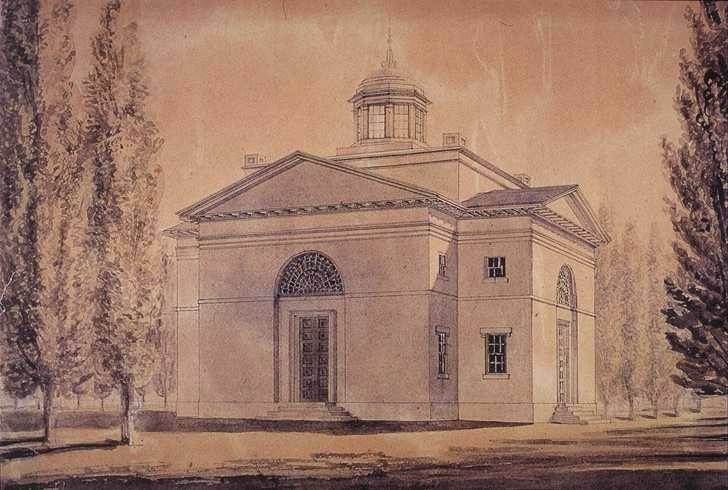

St, John's Church, Washington D.C.

Princeton University. Property of the Trustees of Princeton University.

Source: Unknown

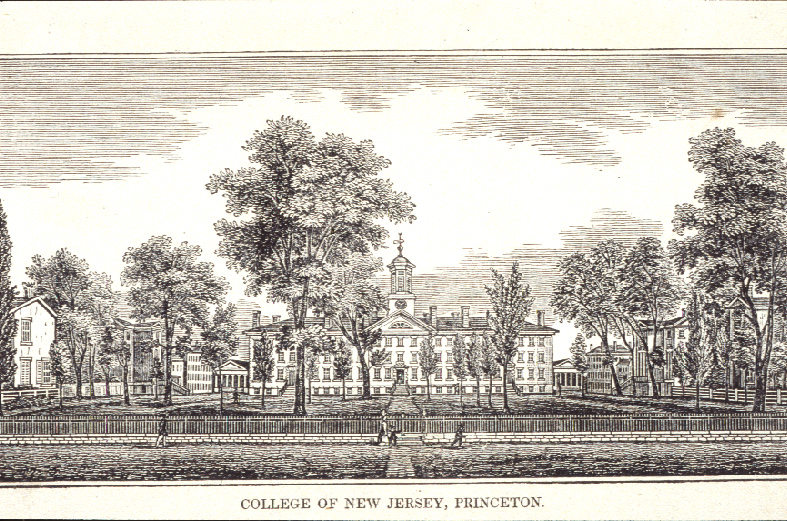

View of front Campus circa 1842

Princeton University. Property of the Trustees of Princeton University.

Source: Unknown.

With the elegant renovation of Nassau Hall and the addition of Philosophical and Geological Halls, the front campus took on a pleasantly symmetrical form. A drawing from the early 1800s shows how the College looked from Nassau Street: The Vice-President's House is at the northeast corner, and behind it Philosophical Hall.

To the west of Nassau Hall stands the house constructed in 1827 for the Professor of Languages, and completing the scene is Geological Hall. Out of view to the northwest are the President's House and two other College structures: the Servant's House and the Market House.

View of front campus circa1825-1835

Princeton University. Property of the Trustees of Princeton University.

Source: Unknown

Another contemporary drawing, showing a northeast view of the campus, contains the President's House.

Pleased with the fruits of their labors, in September 1804 the Trustees ordered that a self-congratulatory circular be printed and distributed. Announcing the "perfect restoration of the College Edifice recently consumed by fire," the circular boasted:

"In comparing the circumstances of the College at the period when they lately solicited the public liberality in its favor, with its present state, they cannot but be deeply affected by the contrast which they witness. At that time the noble structure erected by their predecessors as a nursery for Science and Piety was a heap of ruins; their library was consumed; their pupils were dispersed, and they were wholly destitute of funds, either to replace their losses by the fire, or to provide for the instruction of the youth. They now see its buildings not only restored and improved, but greatly augmented, three new professorships established, and the number of the pupils increased much beyond what it has ever been at any former period."

Perhaps the rebuilding campaign sapped the College's collective energies. Following on this building spurt, Princeton went through another long hiatus in new construction. It was not until the 1830s that the campus would experience another period of significant growth.

None of Latrobe's renovations of Nassau Hall survives today. But one of the other structures Latrobe designed does remain, and in the Library -- later known as Geological Hall and now called Stanhope -- we can discern Latrobe's distinctive touch. Located to the northwest of Nassau Hall, the Library was designed with a pendant to the east, first known as the Refectory and later as Philosophical Hall.