The Nobel Peace Prize in 1919

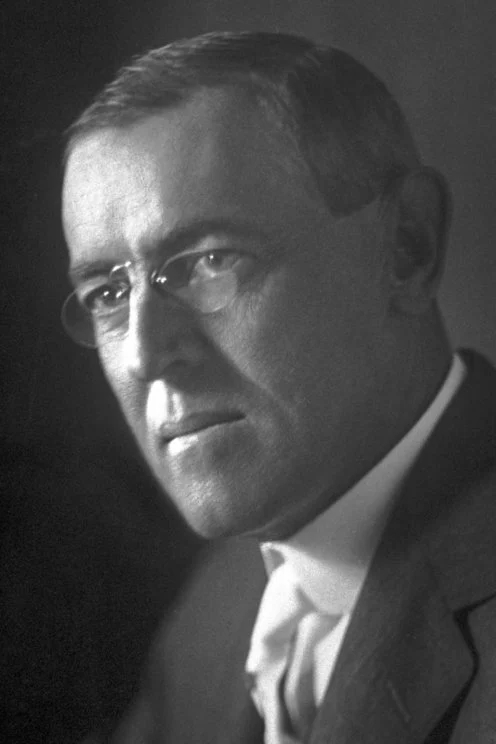

The Nobel Peace Prize 1919 was awarded to Thomas Woodrow Wilson "for his role as founder of the League of Nations."

Woodrow Wilson received his Nobel Prize one year later, in 1920. During the selection process in 1919, the Norwegian Nobel Committee decided that none of the year's nominations met the criteria as outlined in the will of Alfred Nobel. According to the Nobel Foundation's statutes, the Nobel Prize can in such a case be reserved until the following year, and this statute was then applied. Woodrow Wilson therefore received his Nobel Prize for 1919 one year later, in 1920.

Father of the League of Nations

President Woodrow Wilson of the United States won the Peace Prize for 1919 as the leading architect behind the League of Nations. It was to ensure world peace after the slaughter of millions of people in the First World War.

After the outbreak of war in 1914, it was Wilson's policy to keep the United States out. But Germany's unrestricted submarine offensive sank American ships, and in 1917 Wilson took the United States into the war. While severely critical of those at home who opposed the war, he presented his Fourteen Points program for peace. Wilson recommended national self-government for oppressed peoples, a conciliatory attitude to losers in the war, and a league of nations to ensure post-war peace.

The peace negotiations in Paris were a disappointment to Wilson. Britain and France insisted that Germany must pay an enormous indemnity and accept the blame for the war. Subsequently the Senate refused to approve US membership of the new League of Nations. For this reason, there was disagreement about Wilson in the Nobel Committee, until a majority decided to give him the Prize.

[Curator’s note: The following material quotes and paraphrases extensively from articles posted by the Nobel Prize Committee, the Daily Princetonian and the Town Topics; see Sources below for details.]

Early life

Thomas Woodrow Wilson was born on December 28, 1856 in Staunton, Virginia, to parents of a predominantly Scottish heritage. Since his father was a Presbyterian minister and his mother the daughter of a Presbyterian minister, Woodrow was raised in a pious and academic household.

Princeton and University of Virginia Law

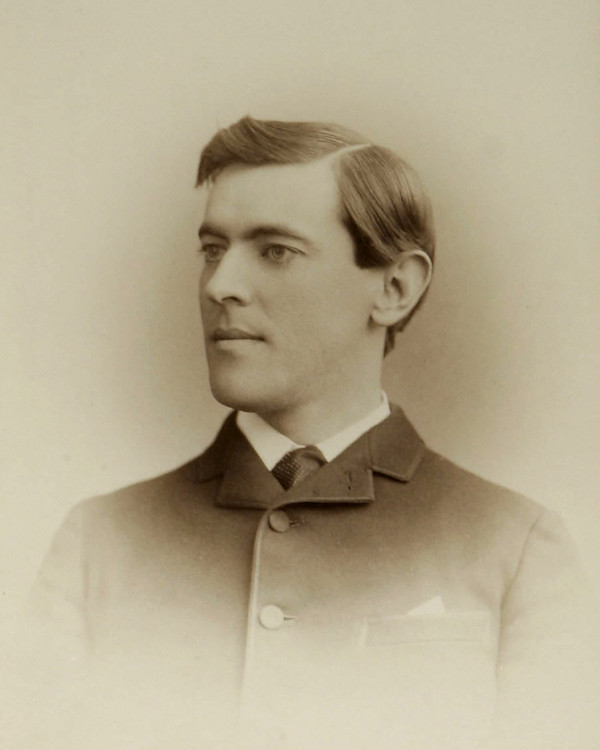

Wilson c. 1875

Wilson attended Davison College in North Carolina for the 1873–74 school year, but transferred as a freshman to the College of New Jersey (Princeton University). He studied political philosophy and history, joined the Phi Kappa Psi fraternity, and was active in the Whig literary and debating society. He was also elected secretary of the school's football association, president of the school's baseball association, and managing editor of the student newspaper.

After graduating from Princeton in 1879, Wilson attended the University of Virginia School of Law, where he was involved in the Virginia Glee Club and served as president of the Jefferson Literary and Debating Society. After poor health forced his withdrawal from the University of Virginia, he continued to study law on his own while living with his parents in Wilmington, North Carolina.

Wilson was admitted to the Georgia bar and made a brief attempt at establishing a legal practice in Atlanta in 1882. Though he found legal history and substantive jurisprudence interesting, he abhorred the day-to-day procedural aspects. After less than a year, he abandoned his legal practice to pursue the study of political science and history at Johns Hopkins.

His doctoral dissertation, “Congressional Government,” led to teaching positions at Bryn Mawr, Wesleyan, and finally Princeton.

As professor of jurisprudence, Wilson built up a strong prelaw curriculum. He was soon voted most popular teacher and became friend and counselor to countless students who were attracted by his warmth and high-mindedness. During the sesquicentennial celebration of 1896, he delivered the keynote address: “Princeton in the Nation’s Service.”

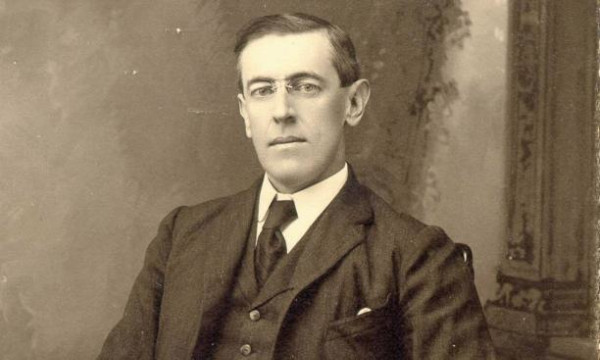

President of Princeton University

President of Princeton

When he became president, Wilson proposed a $12.5 million program to transform Princeton into a full-scale university. At the time this was a staggering sum, almost 25 times greater than the annual budget, but the trustees approved it immediately.

He began by creating an administrative structure — departments of instruction with heads that reported directly to him. In place of the aimless elective system, he substituted a unified curriculum of general studies during the freshman and sophomore years, capped by concentrated study in one discipline (the academic “major”) during the junior and senior years. He also added an honors program for able and ambitious students. Wilson tightened academic standards so severely that enrollment declined sharply until 1907. A cartoon in the exhibition from Tiger magazine during that period shows Wilson sitting on the steps of Nassau Hall covered in cobwebs, implying that the president would be on campus alone if his practices continued.

Supported by the first all-out alumni fundraising campaign in Princeton’s history, he doubled the faculty overnight through the appointment of almost 50 young assistant professors, called “preceptors,” charged with guiding students through assigned reading and small group discussion. With a remarkable eye for quality, he assembled a youthful faculty with unusual talent and zest for teaching.

In strengthening the science program, Wilson called for basic, unfettered, “pure” research. In the field of religion, he made biblical instruction a scholarly subject. He broke the hold of conservative Presbyterians over the board of trustees, and appointed the first Jew and the first Roman Catholic to the faculty.

Before the end of his term, he authorized fellow members of the Class of 1879 to cast two heroic bronze tigers for the front steps of Nassau Hall.

Wilson’s presidency began to unravel in 1906 when he tried to get rid of the eating clubs on Prospect Avenue because they were "detrimental to the intellectual life and social democracy of the University," according to A Princeton Companion.

He proposed moving the students into colleges, also known as quadrangles, in which undergraduates of all four classes would live with their own recreational facilities and resident faculty masters. Membership would be assignment or lot. But Wilson's Quad Plan was met with opposition from Princeton's alumni. In October 1907, due to the intensity of alumni opposition, the Board of Trustees instructed Wilson to withdraw the Quad Plan. Late in his tenure, Wilson had a confrontation with Andrew Fleming West, dean of the graduate school, and also West's ally ex-President Grover Cleveland, who was a trustee. Wilson wanted to integrate a proposed graduate school building into the campus core, while West preferred a more distant campus site. In 1909, Princeton's board accepted a gift made to the graduate school campaign subject to the graduate school being located off campus.

He is perhaps best remembered for coining the phrase, “Princeton in the Nation's Service," in a speech during the University's sesquicentennial celebration in 1896 and again during his inauguration. The phrase, later expanded by Princeton’s 18th President Harold Shapiro, became Princeton’s motto.

Wilson's efforts to reform Princeton earned him national notoriety, but they also took a toll on his health. In 1906, Wilson awoke to find himself blind in the left eye, the result of a blood clot and hypertension. Modern medical opinion surmises Wilson had had a stroke—he later was diagnosed, as his father had been, with hardening of the arteries.

Wilson became disenchanted with his job due to the resistance to his recommendations, and he began considering a run for office. Prior to the 1908 Democratic National Convention, Wilson dropped hints to some influential players in the Democratic Party of his interest in the ticket. While he had no real expectations of being placed on the ticket, he left instructions that he should not be offered the vice presidential nomination. Party regulars considered his ideas politically as well as geographically detached and fanciful, but the seeds had been sown. McGeorge Bundy in 1956 described Wilson's contribution to Princeton: "Wilson was right in his conviction that Princeton must be more than a wonderfully pleasant and decent home for nice young men; it has been more ever since his time".

As president of Princeton University from 1902 to 1910, Wilson became widely known for his ideas on reforming education. In pursuit of his idealized intellectual life for democratically chosen students, he wanted to change the admission system, the pedagogical system, the social system, even the architectural layout of the campus. But Wilson was a thinker who needed to act. So he entered politics and as governor of the State of New Jersey from 1911 to 1913 distinguished himself once again as a reformer.

[Curator's note: Wilson's legacy as President of Princeton has been re-examined in light of his "significant and consequential racism even by the standards of his own time."]

Wilson as NJ Governor

In 1910 Wilson accepted the Democratic nomination for governor of New Jersey. He won the election in a landslide. His ambitious and successful Progressive agenda, centered around protecting the public from exploitation by trusts, earned him national recognition, and in 1912 he won the Democratic nomination for president. Wilson's "New Freedom" platform, focused on revitalization of the American economy, won him the presidency with 435 electoral votes out of 531, and Democratic majorities in both houses of Congress.

Wilson US President

Wilson won the presidential election of 1912 when William Howard Taft and Theodore Roosevelt split the Republican vote. Upon taking office he set about instituting the reforms he had outlined in his book The New Freedom, including the changing of the tariff, the revising of the banking system, the checking of monopolies and fraudulent advertising, the prohibiting of unfair business practices, and the like.

But the attention of this man of peace was forced to turn to war. In the early days of World War I, Wilson was determined to maintain neutrality. He protested British as well as German acts; he offered mediation to both sides but was rebuffed. The American electorate in 1916, reacting to the slogan “He kept us out of war”, reelected Wilson to the presidency. However, in 1917 the issue of freedom of the seas compelled a decisive change. On January 31 Germany announced that “unrestricted submarine warfare” was already started; on March 27, after four American ships had been sunk, Wilson decided to ask for a declaration of war; on April 2 he made the formal request to Congress; and on April 6 the Congress granted it.

Wilson never doubted the outcome. He mobilized a nation – its manpower, its industry, its commerce, its agriculture. He was himself the chief mover in the propaganda war. His speech to Congress on January 8, 1918, on the “Fourteen Points” was a decisive stroke in winning that war, for people everywhere saw in his peace aims the vision of a world in which freedom, justice, and peace could flourish.

Although at the apogee of his fame when the 1919 Peace Conference assembled in Versailles, Wilson failed to carry his total conception of an ideal peace, but he did secure the adoption of the Covenant of the League of Nations. His major failure, however, was suffered at home when the Senate declined to approve American acceptance of the League of Nations. This stunning defeat resulted from his losing control of Congress after he had made the congressional election of 1918 virtually a vote of confidence, from his failure to appoint to the American peace delegation those who could speak for the Republican Party or for the Senate, from his unwillingness to compromise when some minor compromises might well have carried the day, from his physical incapacity in the days just prior to the vote.

The cause of this physical incapacity was the strain of the massive effort he made to obtain the support of the American people for the ratification of the Covenant of the League. After a speech in Pueblo, Colorado, on September 25, 1919, he collapsed and a week later suffered a cerebral hemorrhage from the effects of which he never fully recovered. An invalid, he completed the remaining seventeen months of his term of office and lived in retirement for the last three years of his life.

Wilson served as Princeton's 13th president, America’s 28th president and achieved a host of domestic reforms, including the creation of the Federal Reserve System, the income tax, and the Federal Trade Commission, which ushered in a new era of government regulation. He led the United States through World War I; his Fourteen Points remain an outstanding liberal expression of international relations, though he failed to gain U.S. entry into the League of Nations.

Woodrow Wilson Prize

In 1956, the Woodrow Wilson Prize was created to recognize Princeton’s outstanding alumnus working in "the nation's service." A recipient will be honored each year with the Woodrow Wilson Prize, established this year by an anonymous donor. Trustees of the university late 'this summer accepted a capital gift of $35,000 to maintain the prize in Wilson’s honor. Origin of the prize is Wilson’s famous statement, “Princeton in the nation's service," made at the Princeton Sesquicentennial Celebration in 1896. The first presentation of the $1000 cash award was made in February at the annual mid-winter meeting of the Princeton National Alumni Association.

Named to the initial selection committee were Chandler Cudlipp '19, president of the National Alumni Association; August Heckscher, president of the Woodrow Wilson Foundation, and Professor Dana G. Munro, director of the Woodrow Wilson 'School of Public and International Affairs. A member of the faculty will also serve on the committee. "It is the donor's intent," President Dodds said, "that the awards of the Wilson Prize . . . should be made on the basis of a broad definition of the nation's service, including service to education."

Woodrow Wilson retired to Washington DC and died on February 3, 1924.

SOURCES

• The Nobel Peace Prize 1919. NobelPrize.org.

• Woodrow Wilson – Facts. NobelPrize.org.

• Firestone Exhibit Chronicles Wilson From Student Days Town Topics, 15 May 2002

• Alumni Prize Given To Honor Wilson. Daily Princetonian, Volume 80, Number 83, 19 September 1956

OTHER RESOURCES