The Nobel Prize in Literature 1936

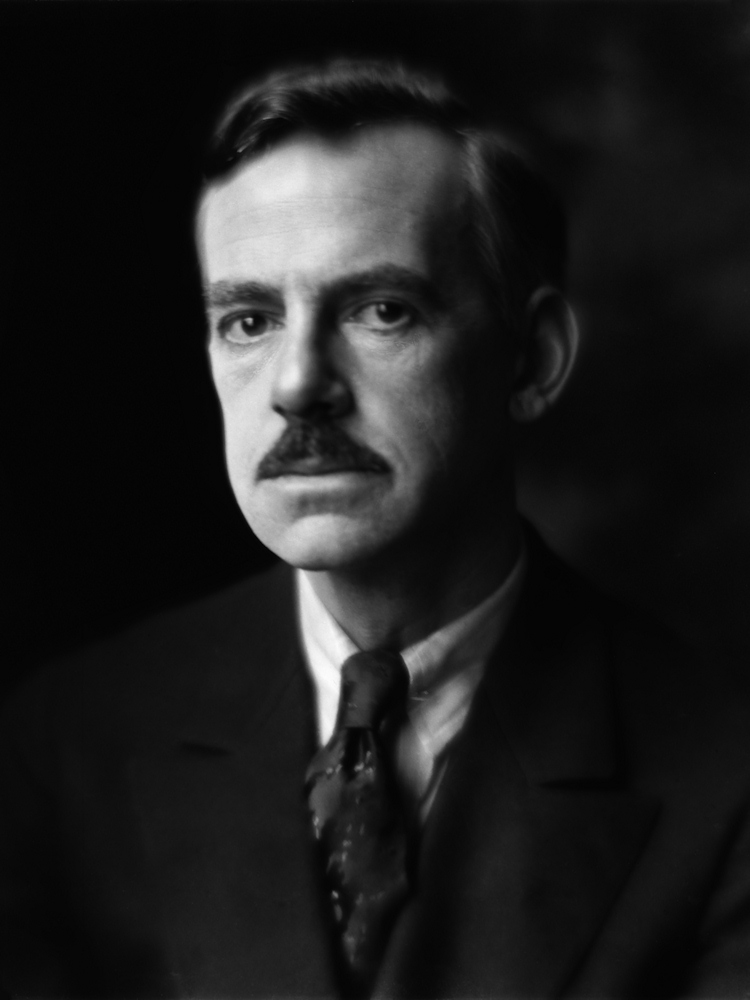

The Nobel Prize in Literature 1936 was awarded to Eugene Gladstone O'Neill "for the power, honesty and deep-felt emotions of his dramatic works, which embody an original concept of tragedy."

Eugene O'Neill received his Nobel Prize one year later, in 1937. During the selection process in 1936, the Nobel Committee for Literature decided that none of the year's nominations met the criteria as outlined in the will of Alfred Nobel. According to the Nobel Foundation's statutes, the Nobel Prize can in such a case be reserved until the following year, and this statute was then applied. Eugene O'Neill therefore received his Nobel Prize for 1936 one year later, in 1937.

Work

O’Neill was awarded the Pulitzer Prize three times, first for Beyond the Horizon (1920), his debut play. After his death O’Neill also received the award for his best known and most often produced work, Long Day’s Journey into Night. It was published five years after his death and had its world premiere at the Royal Dramatic Theatre in Stockholm. The autobiographical play describes the dysfunctional Tyrone family grappling with addiction problems. In a writing career that revolves around human tragedies, Ah, Wilderness is O’Neill’s only well-known comedy.

[Curator’s note: The following material quotes and paraphrases extensively from articles posted by the Nobel Prize Committee, the Daily Princetonian, Princeton Alumni Weekly; see Sources below for details.]

Early life

Eugene Gladstone O’Neill was born on October 16th, 1888, in New York City, son of James O’Neill, the popular romantic actor. “The first seven years of my life were spent mostly in hotels and railroad trains, my mother accompanying my father on his tours of the United States, although she never was an actress, disliked the theatre, and held aloof from its people.”

From the age of seven to thirteen, O’Neill attended Catholic schools. Then four years at a non-sectarian preparatory school, followed by one year (1906-1907) at Princeton University.

Princeton for a Freshman Year

In the fall of 1906, a mopheaded, bookish young man with a taste for absinthe began his Princeton career — a career he would terminate only 10 months later. His name was Eugene O’Neill. The story of the dramatist's freshman year at Princeton occupies 12 pages of Louis Sheaffer's recently published “O’Neill: Son and Playwright" probably one of the most authoritative biographies of O’Neill’s early life. "Princeton was all play and no work," Sheaffer quotes O’Neill as saying, "I think that G. ‘felt instinctively' that we were not in touch with real life or on the trail of real things." Sheaffer spent seven years meticulously reviewing this book. For the chapter on Princeton, he wrote each of the 180 surviving members of the Class of 1910, and carried on extensive correspondence with the members who knew O’Neill.

One of O’Neill’s chums who used to eat with him in Commons said that he was "almost always reading when I saw him." But O’Neill was not a student at heart; he did a minimum of school work and when he left at the end of the year he was already barred from several exams for cutting too many classes. A dean congratulated him for "cramming four years of play into one." Sheaffer discounts the famous story that O’Neill threw a beer bottle through a window of Woodrow Wilson's house. Sheaffer claims O’Neill, staggering home from one of his frequent soirees in Trenton, decided to vent his wrath on the house of a certain railroad district supervisor because the Princeton Junction shuttle wasn't running late that night.

It was the supervisor, not the president, who had his window smashed by the well-aimed beer bottle. Later in life, O’Neill was offered many honorary degrees, but he only accepted one, saying, "This one honorary Yale Litt. D. I have will last me a lifetime--although if Princeton offered me one (which, of course, will never be) a morbid sense of humor might lead me to go through with that one."

Life after Princeton

In the biographical piece under his Nobel Prize award in 1937, he writes:

After expulsion from Princeton, I led a restless, wandering life for several years, working at various occupations. I was a secretary of a small mail order house in New York for a while, then went on a gold prospecting expedition in the wilds of Spanish Honduras. Found no gold but contracted malarial fever. Returned to the United States and worked for a time as assistant manager of a theatrical company on tour. After this, a period in which I went to sea, and also worked in Buenos Aires for the Westinghouse Electrical Co., Swift Packing Co., and Singer Sewing Machine Co. Never held a job long. Was either fired quickly or left quickly. Finished my experience as a sailor as able-bodied seaman on the American Line of transatlantic liners. After this, was an actor in vaudeville for a short time, and reporter on a small town newspaper. At the end of 1912 my health broke down and I spent six months in a tuberculosis sanatorium.

Writing Plays

O’Neill began to write plays in the Fall of 1913. He wrote the one-act Bound East for Cardiff in the Spring of 1914. This is the only one of the plays written in this period which has any merit.

In the Fall of 1914, I entered Harvard University to attend the course in dramatic technique given by Professor George Baker. I left after one year and did not complete the course.

The Fall of 1916 marked the first production of a play of mine in New York – Bound East for Cardiff – which was on the opening bill of the Provincetown Players. In the next few years this theatre put on nearly all my short plays, but it was not until 1920 that a long play Beyond the Horizon was produced in New York. It was given on Broadway by a commercial management – but, at first, only as a special matinee attraction with four afternoon performances a week. However, some of the critics praised the play and it was soon given a theatre for a regular run, and later in the year was awarded the Pulitzer Prize. I received this prize again in 1922 for Anna Christie and for the third time in 1928 for Strange Interlude.

"The following is a list of all my published and produced plays which are worth mentioning, with the year in which they were written:"

Bound East for Cardiff (1914), Before Breakfast (1916), The Long Voyage Home (1917), In the Zone (1917), The Moon of the Carabbees (1917), Ile (1917), The Rope (1918), Beyond the Horizon (1918), The Dreamy Kid (1918), Where the Cross is Made (1918), The Straw (1919), Gold (1920), Anna Christie (1920), The Emperor Jones (1920), Different (1920), The First Man (1921), The Fountain (1921-22), The Hairy Ape (1921), Welded (1922), All God’s Chillun Got Wings (1923), Desire Under the Elms (1924), Marco Millions (1923-25), The Great God Brown (1925), Lazarus Laughed (1926), Strange Interlude (1926-27), Dynamo (1928), Mourning Becomes Electra (1929-31) , Ah, Wilderness (1932), Days Without End (1932-33).

Biographical note on Eugene O’Neill

After an active career of writing and supervising the New York productions of his own works, O’Neill (1888-1953) published only two new plays between 1934 and the time of his death. In The Iceman Cometh (1946), he exposed a “prophet’s” battle against the last pipedreams of a group of derelicts as another pipedream and managed to infuse into the "Lower Depths” atmosphere a sense of the tragic. A Moon for the Misbegotten (1952) contains a strong autobiographical content, which it shares with Long Day’s Journey into Night (posth. 1956), one of O’Neill’s most important works. The latter play, written, according to O’Neill, “in tears and blood… with deep pity and understanding and forgiveness for all the four haunted Tyrones”, had its premiere at the Royal Dramatic Theatre in Stockholm. Sweden grew into an O’Neill centre with the first productions of the one-act play Hughie (posth. 1959) as well as A Touch of the Poet (posth. 1958) and an adapted version of More Stately Mansions (posth. 1962 ) – both plays being parts of an unfinished cycle in which O’Neill returned to his earlier attempts at making psychological analysis dramatically effective.

High praise

"No man writing for the modern theatre has done more to extend its horizons than Eugene O’Neill" asserted Professor Edward L. Hubler of Princeton’s English Department in his fourth and last talk on 20th-century English drama. With this address on “Eugene O’Neill” the 12-lecture extracurricular course on contemporary English literature was brought to a close.

The lecturer stated that, to find a working comparison with O’Neill, the student has to go back to Shakespeare and the Greeks, the only ones in the speaker's opinion who have produced first-order tragedy. He explained that while he did not intend to compare the modern playwright with the masters, he would say that no writer for the past 300 years has come as close to the ideal.

O’Neill was described as "an experimental artist who has used as many theatre tricks as he could master, and whose preoccupation with giving his characters significance beyond their proper selves has led him into fresh fields of theatrical art."

Eugene O’Neill died on November 27, 1953.

SOURCES

• The Nobel Prize in Literature 1936. NobelPrize.org.

• Eugene O'Neill – Facts. NobelPrize.org.

• Eugene O'Neill Biography Published Daily Princetonian, Volume 92, Number 107, 1 November 1968

OTHER RESOURCES