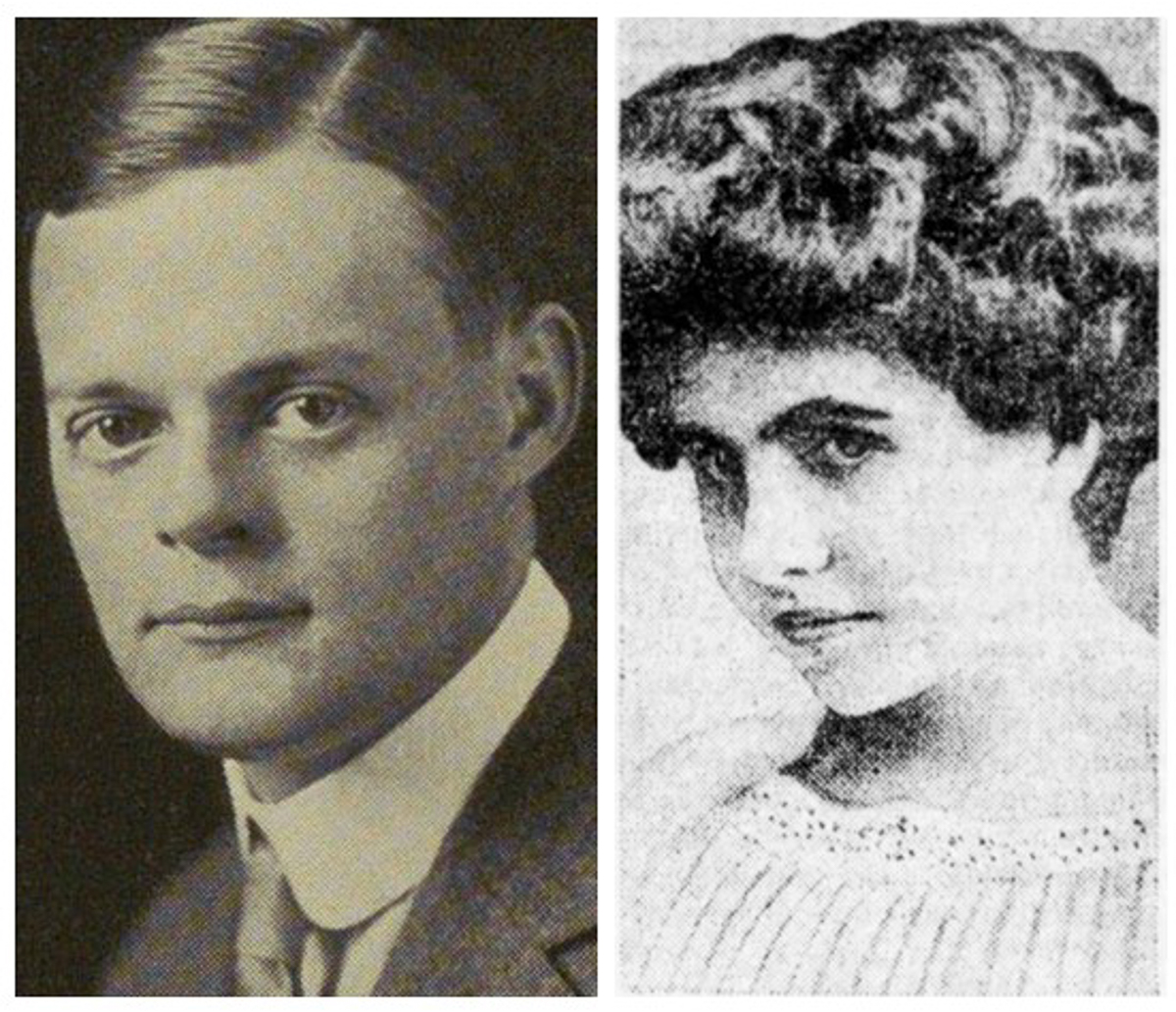

During a 1913 march by Suffragettes from New York City through Princeton en route to Washington D.C., William Whitfield Cator Jr. 1916 joined the march and proposed marriage to the beautiful young marcher Phoebe Hawn. Author Nancy B. Kennedy contacted Princetoniana seeking information about Cator, and kindly agreed to craft the following exhibit. There is much more information available in this exhibit than shown on this page. It can be accessed by clicking on the pictures and the links highlighted in orange.

Tom Swift '76

Chief Curator

Cator and Hawn

On a Thursday evening in February 1913, a small band of weary hikers straggled into Princeton. Making their way down Nassau Street, they were greeted by cries of “Votes for Women!” as crowds of exuberant students poured out from their dining halls onto the street to take in the unusual spectacle.

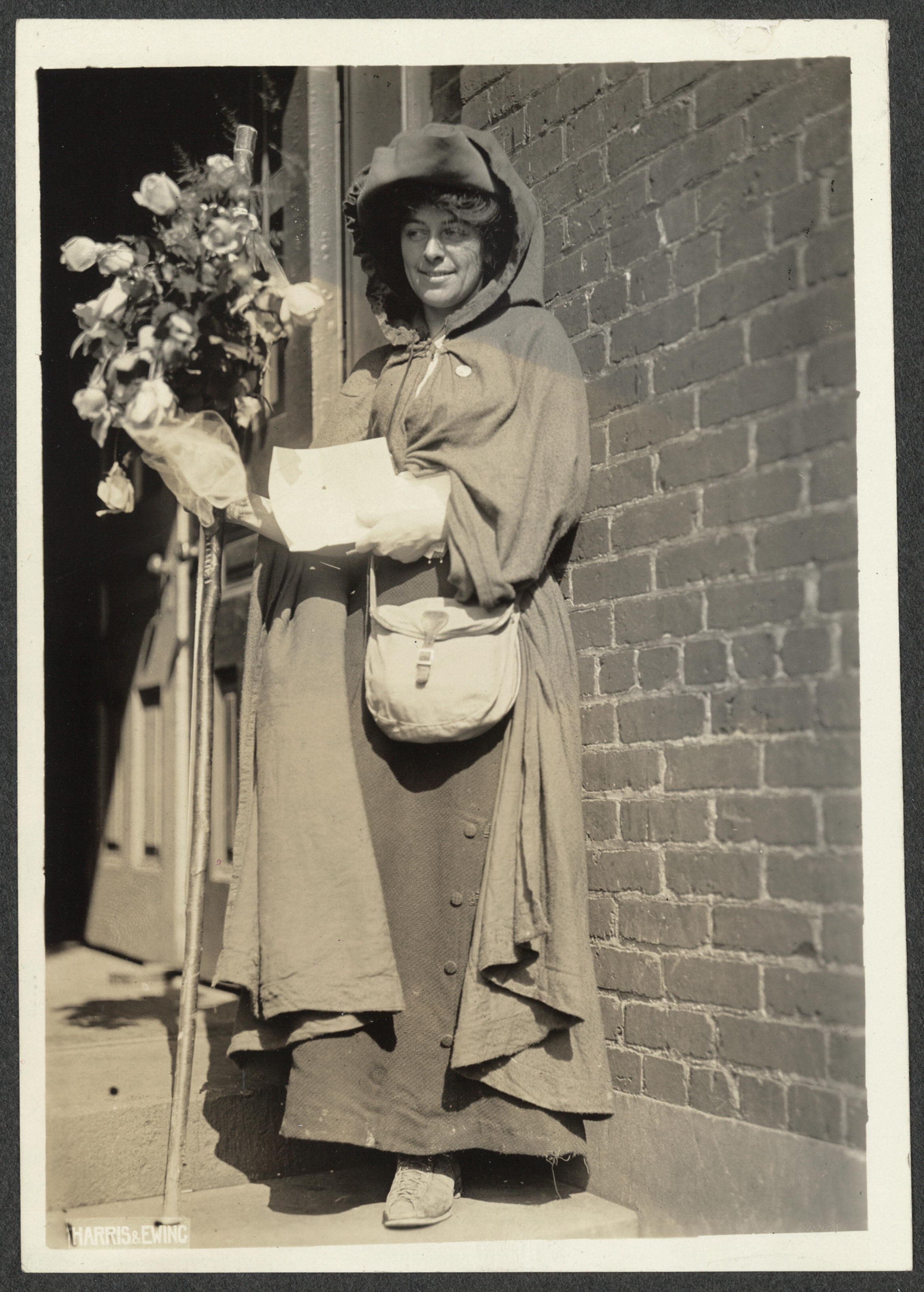

General Jones

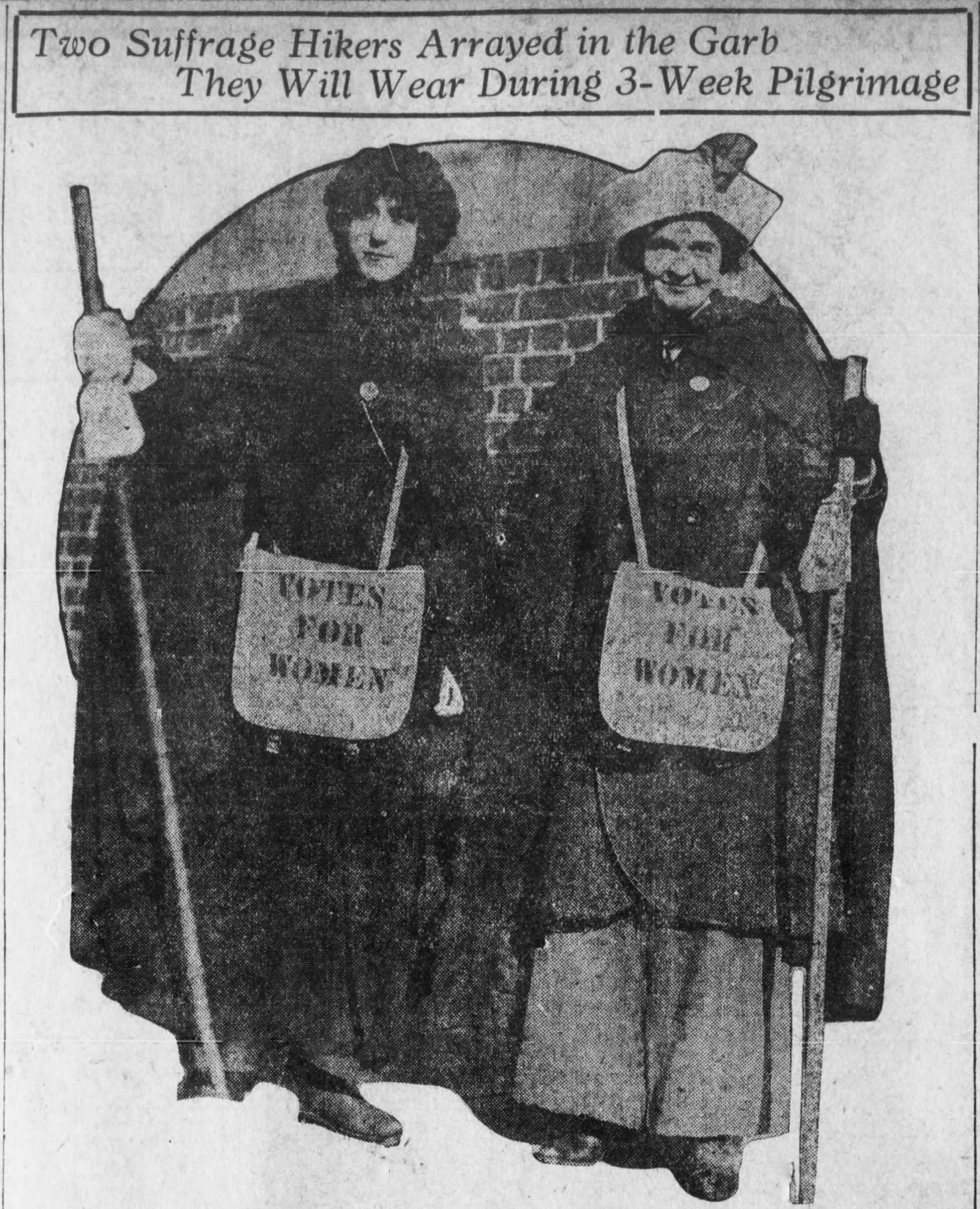

Two suffrage pilgrims

The hikers were “suffrage pilgrims,” a hardy group of women who’d undertaken a grueling, 230-mile hike from New York City to Washington, DC. The suffragists, under the command of General Rosalie Jones, were intent on presenting a petition calling for the woman’s vote to President-elect Woodrow Wilson during his inaugural week. While there, they’d join thousands of their fellow suffragists on Monday, March 3d, for a march down Pennsylvania Avenue (and be attacked by a mob).

Suffrage hikers in Newark

The women had started out on February 12th from Newark and made their way through Elizabeth and on to New Brunswick, an astonishing 27-mile hike. After an overnight stop, the next day’s 17-mile walk would take them to Princeton.

Arrival in Princeton

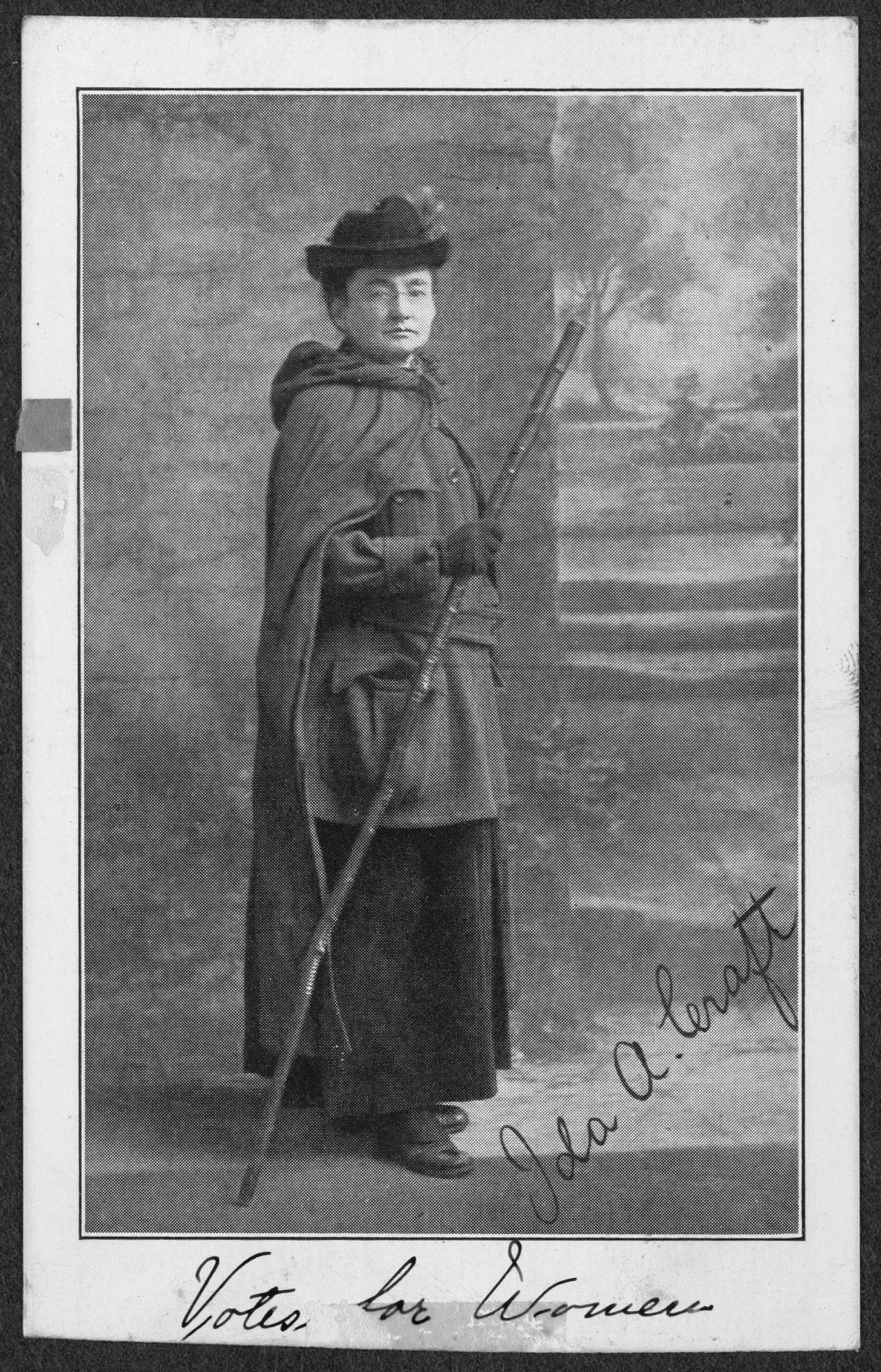

Ida Craft

It was a blustery winter evening when the hikers arrived in town on February 13th. Their pilgrim robes barely shielded them from the cold and every step raised new blisters on their booted feet. But their spirits soared as the students cheered the weary women.

“Just let’s get at those Princeton boys — we’ll make them suffrage workers yet!” exclaimed hiker Ida Craft, the general’s second in command.1

Phoebe on the march

In the fading light of dusk, one particularly enthusiastic student caught sight of a young hiker peering out from under her pilgrim hood. Instantly, he was smitten.

Nicknamed “the Baby Suffragette,” Phoebe Hawn was a blue-eyed, 22-year-old Brooklynite with a coy smile and swooping rolls of raven hair coiled under her hooded pilgrim’s robe. She had recently graduated from Miss Mason’s School for Young Ladies, a private girls school in Tarrytown, New York, and had joined the hike “on a lark,” as she later put it. Her father had founded an elocution school, but Phoebe was quick to say she’d rather speak with her feet.

William at Gilmore

The smitten gentleman, David William Whitfield Cator, Jr. 1916 was a dark-haired, dark-eyed 19-year-old freshman from Baltimore. He had graduated from the prestigious all-boys Gilman School in the Roland Park suburb where his family lived. His was a storied family whose millinery business had provided women like Phoebe with fashionable hats for a hundred years.

At Gilman, William played football and soccer and he continued with soccer at Princeton. At the university, he was a member of Dial Lodge, the American Whig Society, the Southern Club and the Maryland Club. He was known, it was said, for his jolly nature and ready smile.2 He and his roommate that year, William Chauncey “Chaunce” Crawford Jr., another Baltimore boy and a soccer teammate who had also attended Gilman, lived at 14 Park Place in town.

Although William’s nickname until this night had been just plain Bill, forever afterward he became known as “Wee Willie.” Perhaps it was a pet name conferred by the bemused Phoebe. Or perhaps his Princeton classmates crowned him with it. After all, his friends all had colorful nicknames like Bunny, Lefty, Skitch and Froggie.

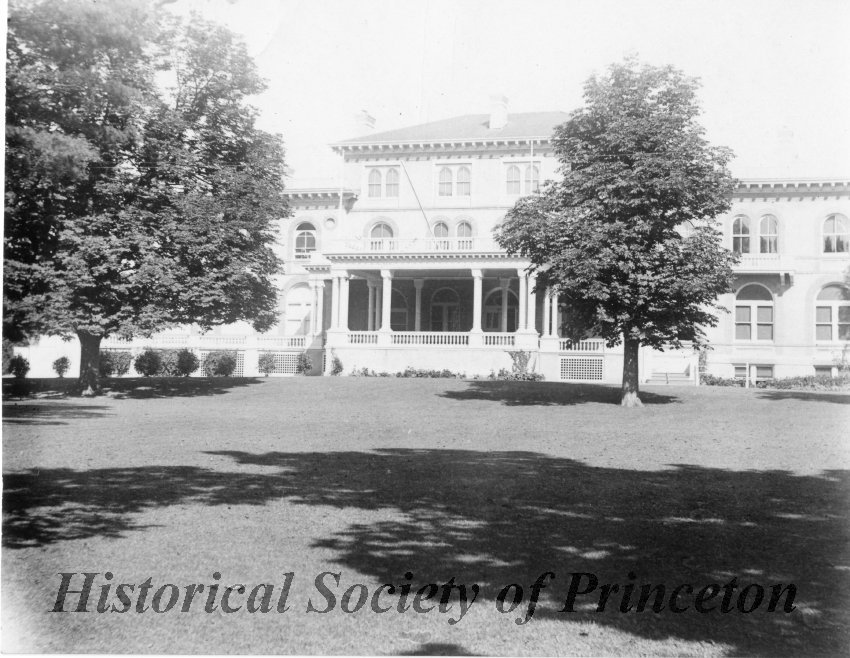

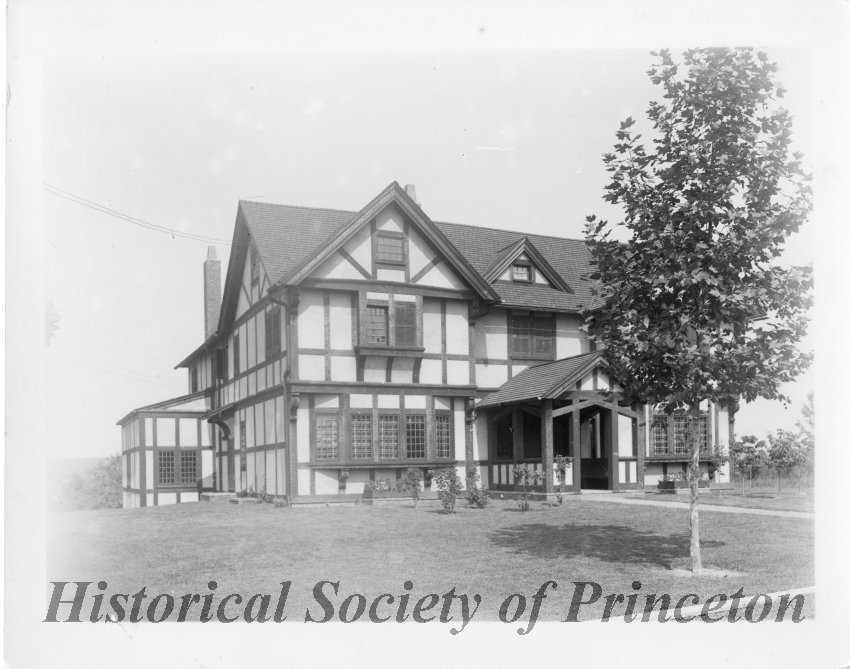

Princeton Inn

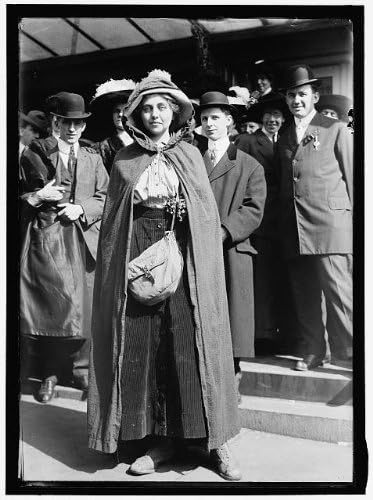

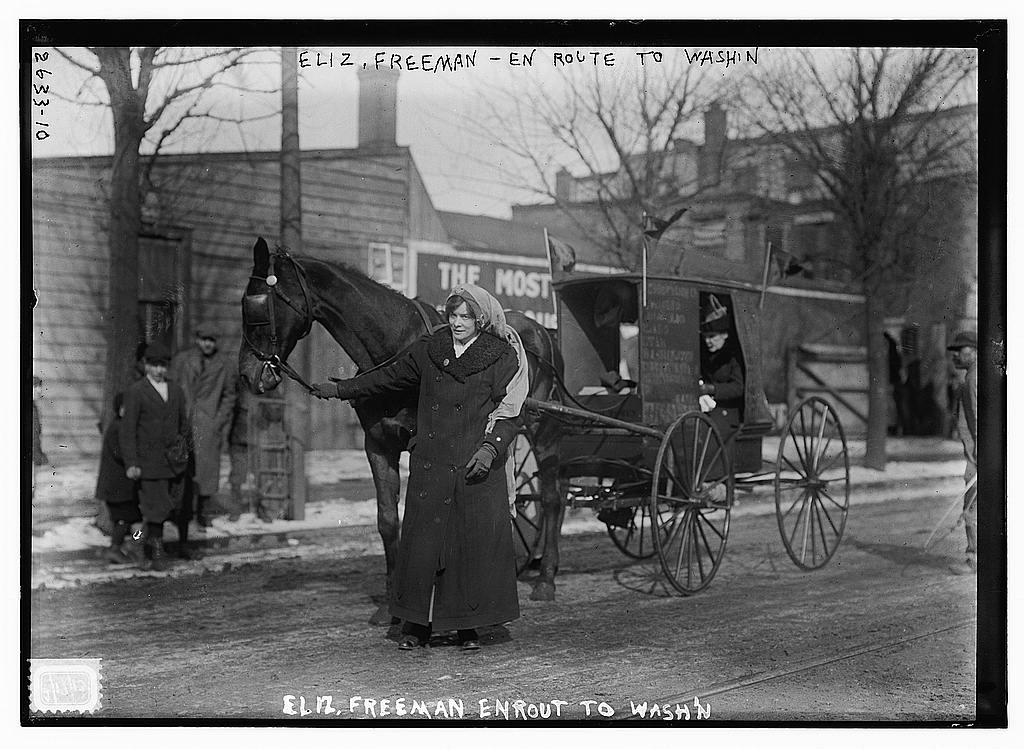

Elizabeth Freeman

Amid the frenzied shouts of suffrage slogans, the bone-tired hikers repaired for a restorative night to the Princeton Inn, an elegant, neoclassical building on Nassau Street standing at the site on which Princeton’s borough hall would later be built. But the students clamored for a speech.

British-born Elizabeth Freeman, who had joined England’s militant suffragette movement in 1905 before moving to the United States, took up the challenge. From the steps of the inn, she spoke for an hour to more than 500 college boys — some whooping and some jeering — before the hikers’ day was done.

Bright and early the next morning, William appeared at the inn, derby hat on his head and cane on his arm. He was there to escort his adored Phoebe along the route.

25 Cleveland Lane

The hardy band headed south for a 10-mile trek to Trenton, where they were to spend the night. On their way out of town, the suffragists stopped to call on president-elect Woodrow Wilson, who was still in residence at 25 Cleveland Lane. They had in hand a letter, which read:

My dear Mr. Wilson,

A small band of “votes-for-women” pilgrims from the States of New York, New Jersey, Pennsylvania, Delaware, Maryland, Virginia and Ohio earnestly request of you an audience of not more than two minutes, as soon after your arrival as possible. They desire to present a message to you.

Thanking you in advance for your courtesy,

I am sincerely,

Rosalie Gardiner Jones3

Rosalie knocked on the door. The servant who answered the door said that, unfortunately, Wilson wasn’t at home. He was in Philadelphia having a tooth filled at the dentist.

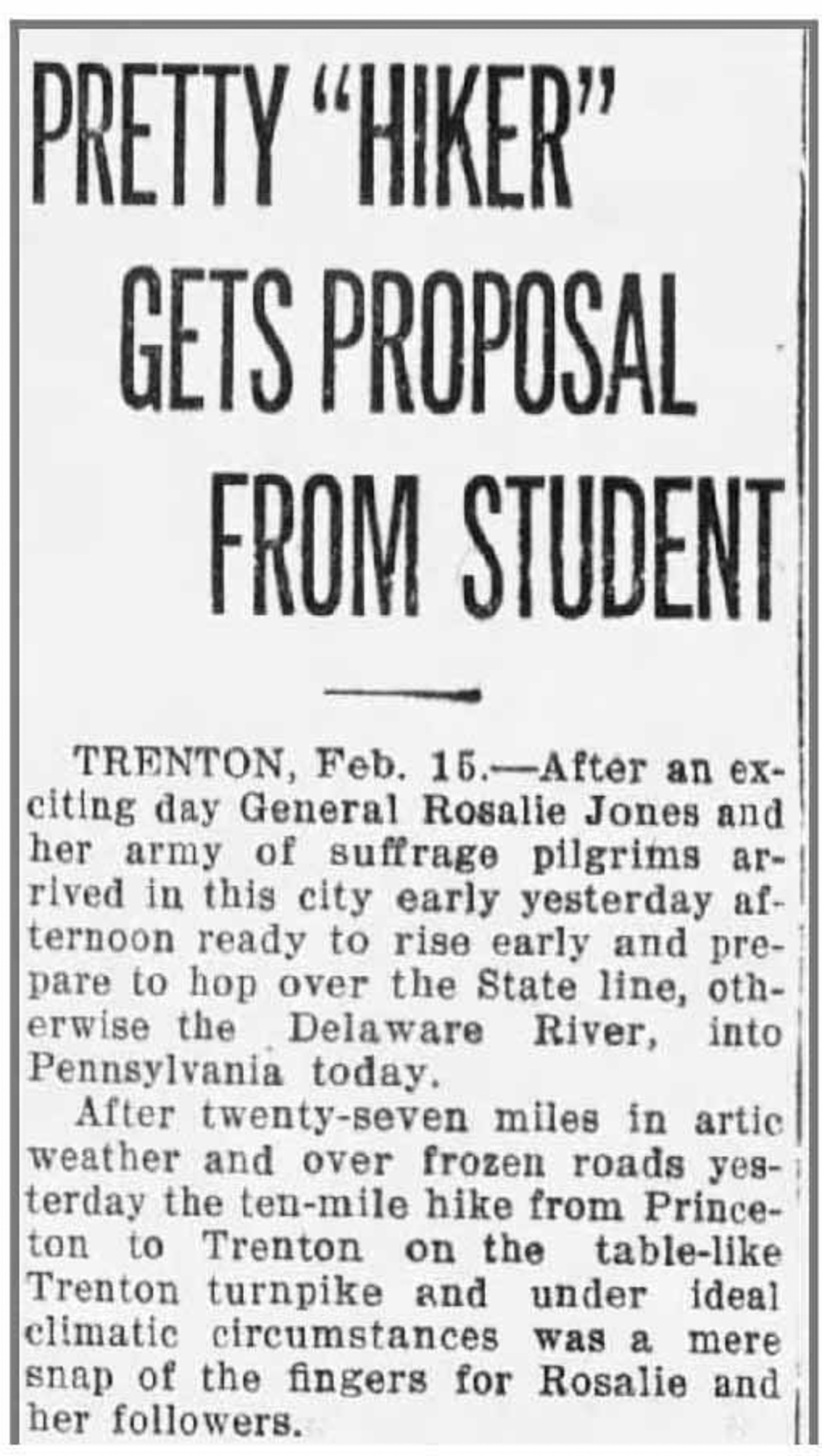

Local news coverage

Disappointed, the women continued on. As they progressed, Willie, the newly-minted suffragent, pressed his suit with Phoebe. Before they’d even reached Lawrenceville, Wee Willie had proposed. For her part, Phoebe took it all in stride, so to speak. “What an excellent joke!” she later said.

Was it a joke? The newspapers speculated that Wee Willie had embarked on a rite of intitiation as a fraternity candidate. He was tasked, the papers hinted, with walking as far as Phoebe did and proposing at least once a day. If this was the truth, William would not have said so. Like all incoming students, he had signed a pledge vowing not to join a “secret society,” as the officially banned fraternities were known. Perhaps he was simply struck by cupid’s arrow on the eve of St. Valentine’s Day.

Alas, Phoebe wasn’t similarly struck.

“He’s just the dearest and sweetest boy I ever met,” Phoebe said later.4 “But with everyone all ready to ring the wedding bells, why, I told Mr. Cator for goodness sake to go straight back home.”

But Mr. Cator did not go home. On the band marched.

Word had reached Lawrenceville that the hikers were on the way. They also got wind of the rapturous reception they’d received from the Princeton students, and from students at Rutgers in New Brunswick the day before.

The stirrings of ancient rivalries brewed and the pupils of the Lawrenceville School vowed to outdo their academic neighbors. Some skipped class, while others were released by sympathetic professors.

And they did outdo their rivals, if you believe the newspapers. One headline read: “Prep Pupils Prove that Even Rutgers’s Bow Wow! and Princeton Tigers’ Rah Rah! Are Tame Compared to the Lawlessness of Lawrenceville School’s Law! Law! Yell”5

After an overnight stop in Trenton, the women, with Wee Willie still at Phoebe’s side, trekked eight miles to Bordentown. On the outskirts of town, the hikers were welcomed by a marching band of uniformed young men and escorted to the Bordentown Military Institute, where a luncheon had been prepared for them.

While the commandant of the high school, Col. Thompson Hoadley Landon, gave a welcoming speech, a door to the dining hall burst open. A squadron of burly Princeton men entered and scanned the room, their eyes coming to rest on Wee Willie. The university had dispatched them by auto to kidnap the errant freshman and escort him back to Princeton.6

Poor lovelorn William reluctantly followed his classmates back to Princeton. For his brash act, the university considered expelling him. But in the end, after it elicited sworn statements from Phoebe and from reporters covering the hike, the university judged that the wayward gent had besmirched neither the good name of the fair Phoebe nor of Princeton itself (whose faculty was decidedly anti-suffrage).

Eight months later, Wee Willie almost certainly saw the notice of Phoebe’s engagement to Donald Stanton Northrup of Johannesburg, South Africa, a graduate of the Pratt Institute who held a degree in electrical mining engineering. They might have met in Binghamton, New York, where Donald’s family had once lived. They married in 1914 and made their home in Syracuse, where they welcomed a daughter, Jane, in 1917. However, the couple separated in 1922, and Phoebe went to live in New York City. She died in 1965 at the age of 74 in Kansas City, Missouri, in the care of her daughter. She had retired as a clerk for Queen of the World Hospital, a short-lived, forward-thinking, fully integrated hospital staffed by and serving people of all races.7

Cator in uniform

William studied for just two years at Princeton, and then left to join the family firm, exactly as his father, William Whitfield Cator Sr. (Class of 1885), had done in his generation. In 1917, he was commissioned in the officers’ reserve corps of the Army, reaching the rank of 1st lieutenant, and he trained infantry troops until the end of World War I.8

Back at Armstrong, Cator & Co., William became the firm’s hiring executive, placing women in manufacturing roles and as models of the company’s hats fashioned in the latest Parisian styles. Perhaps Marian Glantz was one of those models. Or perhaps the two met at the debutante ball where William’s sister, Agnes, was presented to Baltimore society. As a graduate of the Hannah Moore Academy in Westminster, Maryland, Marian would have had a similar education as Phoebe Hawn. William and Marian married in 1925, but children did not follow.

Tragically, William died in 1936, five years after he left the family firm to work as a saleman in the furniture business in High Point, North Carolina. He was just 41 years old, and pneumonia claimed him after an operation to remove his appendix. His body was taken back to Baltimore, where he was buried in Druid Ridge Cemetery. He may have been at university for just two years, but in his obituary, David William Whitfield Cator, Jr., the once-impetuous Wee Willie, was counted a full-fledged Princeton man.

Although the Princeton freshman’s spontaneous walk came to an end in Bordentown, the suffrage hikers pressed on and made it to Washington, where they marched another two and a half miles in the suffrage parade down Pennsylvania Avenue. It was a small band that survived the rigors of the hike, but Phoebe Hawn was among them.

“It was simply glorious, friends, and I wouldn’t have missed it for the world,” she exclaimed later to a standing-room-only crowd at the Brooklyn Daily Eagle building. “It was simply grand, and I’d gladly do it all over again if I had the chance.”9

1 "Suffrage Marathon Band Encounters and Overcomes Obstacle," Newark Star-Eagle, February 13, 1913, p. 3.

2 Notes from his classmates reporting his death in the Princeton Alumni Weekly, Vol. XXXVI, No. 28 (May 1, 1936).

3 "D. Cupid Trails Suffrage Band,” Washington Herald, February 15, 1913, p. 3.

4 “Phoebe Hawn’s Story of Washington Hike,” Brooklyn Daily Eagle, March 13, 1913, p. 9.

5 Brown, Raymond J. “Suffrage Hike Idea of Young America’s Prowess Gets Boost.” Newark Evening Star, February 14, 1913, pp. 1, 9.

6 “Hiking Pilgrims Hurry to Beds at Burlington,” Philadelphia Enquirer, February 16, 1913, pp. 1, 17.

7 Queen of the World Hospital operated for just 10 years, from 1955 to 1965. Former President Harry S. Truman was among the guest speakers at its inaugural ceremony. Source: Asia Jones on behalf of Black Archives of Mid-America and Clio Admin. “Queen of the World Hospital (1955-1965),” Clio: Your Guide to History, November 27, 2022.

8 “Maryland Men at Fort Myer Commissioned,” Baltimore Evening Sun, August 11, 1917, p. 12.

9 “Phoebe Hawn’s Story of Washington Hike,” Brooklyn Daily Eagle, March 13, 1913, p. 9.