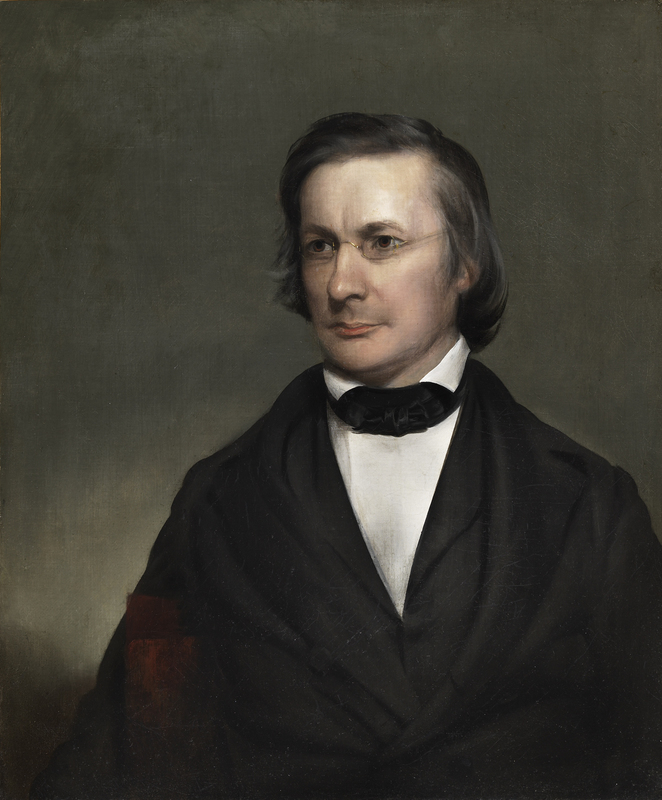

Maclean, John Jr., Class of 1816

Maclean, John Jr., Class of 1816

Princeton University. Property of the Trustees of Princeton University.

Edward Ludlow Mooney, American, 1813–1887 John Maclean (1800–1886), Class of 1816, President (1854–68), 1850 Oil on canvas, 74.5 x 62.2 cm (29 5/16 x 24 1/2 in.) (sight) frame: 99.7 x 87.6 cm (39 1/4 x 34 1/2 in.)

Source: Princeton University, gift of President Maclean

John Maclean, Jr., Class of 1816 (1800-1886) was a member of the faculty for fifty years, serving successively as tutor, professor, vice-president, and tenth president. It was one of the longest associations in Princeton's history.

Son of the first professor of chemistry, John Maclean, Sr., he was born in Princeton and lived there almost all his life, either on or near the Campus.

At his graduation from the College Maclean was the youngest member of his class. Two years later, after earning a divinity degree at the Princeton Theological Seminary, he began his career in the College as a tutor in Greek. He was then eighteen. He became a full professor at twenty-three, vice-president at twenty-nine, and president at fifty-four.

AS VICE-PRESIDENT

Maclean was the mainstay of the thirty-one-year administration of his predecessor, President James Carnahan. When Carnahan, dismayed by the state of affairs he found on his arrival in 1823, thought of resigning, Maclean persuaded him to remain. And when, a few years later, Carnahan thought of closing the College because a further drop in enrollment necessitated cuts in faculty salaries and led to a lowering of morale, Maclean came forward with a bold plan to stop the decline by enlarging and improving the faculty. The trustees accepted his plan and made him vice-president. Maclean secured a few gifts, discovered some funds due the College that had not previously been collected, shifted his own field from mathematics back to classics in order to make way for an able young mathematician, and secured the half-time services of several older men as an inexpensive means of broadening the curriculum. Making the most of the College's limited means, he was able to add to the faculty such outstanding men as Joseph Henry, John Torrey, Stephen Alexander, Albert B. Dod, and James Alexander. These appointments reversed the trend, raising enrollment from 87 in 1829 to 228 ten years later.

IN LOCO PARENTIS

Maclean never married; the time and energy ordinarily expended by a father on his children he gave instead to the students of the College, for whom he quite literally stood in loco parentis. In this he was helped by his two maiden sisters, who lived with him.

He was vigilant in detecting wrongdoing, but sympathetic to the culprit once he was caught. Frequently, he would intercede with the faculty to allow the offender to escape with rustication at a nearby farm. This was a mild enough penalty: returning from rustication, one student reported that he had spent the weeks fishing and "thinking what a good man Doctor Maclean was." Sometimes, if the infraction of the rules was minor, Maclean would merely administer a rebuke; and he seldom rebuked, his students said, without making a friend.

His students also recalled often seeing him in his long cloak, armed with a lamp, a teakettle, and food, on his way to visit a sick student. In case of serious illness the student was brought to his house, and many a parent also found a home with him until the emergency was over. One student, who broke his leg in a fall from a second floor window of West College after the Senior Ball of 1847, was cared for at Maclean's house by Miss Mary Maclean for six weeks.

Maclean was not without a sense of humor. One night two donkeys from a nearby farm were found on the top floor of Nassau Hall. A student on hand at the discovery asked Maclean, with an innocent air, how he thought they had got there. "Through their great anxiety," Maclean replied, "to visit some of their brethren."

He was generous with students in financial straits: over the years he accumulated a drawerful of watches and other articles, un-redeemed pledges for loans he had made from his personal funds.

WORK IN THE COMMUNITY

Maclean showed the same concern for his fellow townsmen. He took a particular interest in the welfare of Negroes in the community, serving as their personal counselor and benefactor and as one of the organizers and supporters of the Witherspoon Street Presbyterian Church, a Negro congregation. Maclean was also the chief support of the Second Presbyterian Church (now united with the First Church), known for many years as "Doctor Maclean's church." A member of the Prison Association, he sometimes walked the ten miles to Trenton on Sundays to conduct services in the State Prison.

He was one of the earliest advocates of public education in New Jersey. An address he delivered in 1829 inspired the state legislature to initiate a system closely following his ideas. Staunch Presbyterian though he was in the affairs of the College, he insisted that the public schools should be completely nonsectarian: "There should be in no case the least interference with the rights of conscience, and no scholar should be required to attend to any lesson relating to morals or religion, to which his parents may be opposed."

PRESIDENCY

Maclean's election in 1854 as President Carnahan's successor was as much a reward for previous service as it was an expectation of future achievement. Indeed, there was a strong feeling among the trustees that the College needed a leader of greater distinction, and many favored calling Joseph Henry to the post. But Henry declined to be a candidate and urged the election of Maclean, stressing particularly his "untiring devotion to the interest of the college."

As it turned out, Maclean's "untiring devotion" was just what the College needed for the two extraordinary challenges it had to face during the years he was president: the loss of Nassau Hall by fire in 1855 and the drop of enrollment during the Civil War. Maclean rallied alumni and friends to contribute funds toward the rebuilding of Nassau Hall, augmented these funds by operating the College on an austerity budget for five years, and then helped liquidate the debt that remained by giving up part of his own salary. More than a third of Princeton's students came from the South, and the College suffered a corresponding drop in enrollment during the Civil War. But Maclean managed to keep his faculty together and to maintain a full program for the students who remained. He and the faculty came out strongly for the Union cause -- more strongly than some of his old student friends from the South thought necessary, but less quickly than some from the North thought appropriate -- and Maclean conveyed to President Lincoln an honorary degree voted by the trustees.

During his presidency, Maclean added a number of good men to the faculty, including the Swiss geographer Arnold Guyot, but as a whole the appointments during this period lacked the luster of those he had contrived earlier. Professor Wertenbaker concluded from his study of the Maclean papers that while Maclean sought good scholars he also looked for good Presbyterians, and that the second desideratum sometimes interfered with the first.

LAST YEARS

On his retirement in 1868, friends bought a house for Maclean at 25 Alexander Street, where he lived out his years with one of his brothers.

In 1877 he completed a two-volume history of the College, an indispensable source of information about Princeton's early years, assigning the royalties to a fund "for the aid of indigent and worthy students engaged in seeking a liberal education."

Although he stayed away from the Campus during term time -- except when he was asked to preach in Chapel -- he made brief appearances there at commencement, and whenever a knot of alumni caught sight of him, a cheer went up for "Johnny." His last appearance -- six weeks before he died -- was at the commencement meeting of the alumni in 1886, the 70th anniversary of his own graduation. As honorary president of the Alumni Association (of which he had been a principal founder and the first secretary), he was given an ovation which, by contemporary accounts, was loud, long, and tearful.

"Some of us old fellows . . . who cheered first and cried afterward," one of them said later, "put a meaning into our action which nobody but Doctor Maclean and ourselves knew. There were secrets between us which he was too good ever to tell, and which, perhaps, we were ashamed to. His full biography will never be written. Its materials would have to be gathered from too many hearts."

John Maclean and slavery

Source: Leitch p. 296 ff