Princeton University. Property of the Trustees of Princeton University.

Princeton Historian and Recording Secretary, Freddie Fox ’39, dubbed Isabella McCosh, the wife of President James McCosh, the “Queen of the Alma Mater” in an article in the Daily Princetonian (Fox, 1974). He quotes James McCosh as saying: “The greatest gift which I got was my dear and excellent wife. She was the daughter of Alexander Guthrie, an eminent physician known all over the country. She has proved to be a most loving wife to me, and has constantly watched over me and my interests. She was an admirable household manager, and enabled me to live handsomely at times on a small income. She had a good deal of the Guthrie character. She was characteristically firm, and did not always yield to me. She advised and assisted in all my work as minister and professor. She visited sick students and looked after their welfare. A hospital has been erected in Princeton College, bearing down her name to future generations." (Leitch, 2015) . Isabella McCosh made impacts on the administration, students and alumni of the all-male College of New Jersey, leaving a legacy that remains in today’s Princeton University. Who is this lady and what legacy did she leave to the future Princeton University?

Scotland

Isabella Guthrie was born in Brechin Scotland on 30 April 1817 to Alexander and Mary Helen Guthrie. She grew up with a brother Alexander, and sisters Clementina and Helen. Her father was an eminent physician and surgeon, having a successful 50-year practice in Brechin. She also was the niece of Dr. Thomas Guthrie, the distinguished Edinburgh clergyman, surgeon and philanthropist who played a key role in the Scottish era of enlightenment and the Great Disruption of the Church of Scotland.

James McCosh

Isabella Guthrie married James McCosh, who was 6 years older, in September of 1845 in Brechin. James McCosh had studied religion, philosophy, and psychology at the University of Glasgow and University of Edinburgh. In his words: "I had a good horse, and set out on the Saturday with my sermons in a saddlebag behind me, preached twice on the Sabbath, and returned home on the Monday." (Princetoniana). Brechin was one of the two locations where he preached each Sabbath. James McCosh also played a significant role in the Great Disruption which he spoke of as “a great event in the history of Scotland” (Princetoniana). He was nationally prominent in the Free Church movement and very successful locally as minister of the new East Free Church in Brechin, which he founded in 1843.

James McCosh was appointed Professor of Logic and Metaphysics at the new Queen’s College in Belfast in 1850. Their daughter Margaret was born in June 1852. Margaret married Dr. David Magie ’59. Their son, Andrew James McCosh ‘80, born in March of 1858, graduated from The College of New Jersey and then studied medicine at the College of Physicians and Surgeons in New York. After completing his internship, he went to the University of Vienna for a year of post graduate study with Dr. Billroth, who was at that time the greatest surgeon in Europe. David died tragically of a fractured skull in December 1908, after he was thrown from a carriage pulled by two spirited horses that were spooked.

College of New Jersey

James McCosh made his first visit to the United States in 1866, as a representative of the Evangelical Alliance. His publications and reputation had proceeded him, and he was well received everywhere he visited. The McCosh family moved to Princeton in 1868, when James McCosh became the 11th President of the College of New Jersey. Their voyage encountered very rough seas and took 14 days to go from London to Sandy Hook, New Jersey. They arrived on 20 October, 1868, and were greeted by students and faculty at the train station. A few days later there was a large formal reception, for the Inauguration, attended by a long list of dignitaries, faculty and alumni. Upon their arrival, the McCosh family moved into the official president’s house, which was the McClean House. Ten years later, 1879, the McCosh family moved to the Prospect House. The Prospect House replaced the McClean House as the official house for the college president. The Prospect House was acquired by the College of New Jersey as part of the 35-acre estate of John Potter, a wealthy merchant from Charleston.

The Civil War had disrupted the flow of students and faculty, resulting in a student body of 281 with less than the usual preparation for college studies. During the next two decades the student body would double and the faculty triple to make the foundation for a university that would be recognized as one of the best in the world. Mrs. McCosh played an active role in orchestrating a social harmony among the students, faculty and administration, based on involvement and trust. There are numerous accounts of the value of her roles. One of her key roles was to use her skills to improve the healthcare at the college.

Healthcare

Healthcare at the College of New Jersey was conducted on an unofficial basis. Prior to the arrival of the McCoshes, the previous President of the College of New Jersey, Dr. John Maclean, Jr. ’16, would personally visit sick students in their rooms, and he moved some of the seriously ill students into the Presidents House to care for them there. A town doctor and specialists in New York City and Philadelphia were also available as needed.

Isabella McCosh took on the task of attending to the ill students during her husband’s administration from 1868 to 1888, and continued this beyond his retirement. She had developed a knowledge of healthcare as the daughter of Dr. Alexander Guthrie, the well-respected physician and surgeon in Brechin, Scotland. Her healthcare services were important to connecting students with the college administration and building lasting relationships with the students, who would become loyal future alumni. It was reported that James McCosh’s personal connections to students “was wonderfully aided by his wife whose gentle solicitude for, and motherly interest in, any that were sick or in need of care made her the sharer in affection that he enjoyed.” (Lee)

There are several first-hand accounts from students whom she had attended. Alexander J. Kerr ‘79, reported, “She had given strict orders to the Scottish college proctor, Matt Goldie, that any student who was ill should be immediately reported to her. Her orders were faithfully obeyed and when any boy was sick. . . . she would take her large basket, place in it one of her own bed sheets, a pillow case, a towel, a wash cloth, some of her own jams and jellies, homemade cookies and tempting cakes and a jug of tea, over which she would place a tea caddy to keep it hot. She would then carry the basket to the sickroom, no matter though she had to climb four flights of iron stairs to do so. . . .she would tap on the door and say, 'May I come in?' But without waiting for a reply she would enter and, after expressing a mother's sympathy, immediately proceed to wash the face, chest and hands of the young man, put the clean sheet on his bed, the pillow case on his pillow, brush his hair and make him as comfortable as possible and encourage him to eat the good things she had brought and to drink a cup of her good tea. Then, sitting down at his desk, she would write a note to his mother, telling her she need not worry about her boy, as 'we are looking after him here.'" (Kerr, 1942)

Philip A. Rollins ’89, who “testified that she saved his foot from amputation after a grievous injury by taking him for a second opinion to her friend, a surgeon in Philadelphia.” (Grahan, 2018), recorded this account of Isabella McCosh: "Every morning she received from the proctor's office a list of the students confined to their rooms by serious malady or injury, and promptly she started her rounds. There would be a gentle knock on the door and a gentle 'May I come in?' Two alumni have told me that, but for her nursing them in their undergraduate days, they would have died of typhoid fever. Three alumni, two of them physicians, have claimed that, but for her nursing, they would have had pneumonia. And it was my personal privilege to hear that knock and query on three occasions at the door of my own room." (Fox, 1974).

Philip A. Rollins ’89 also provided this written imagery of nurse Isabella McCosh when he addressed the Ladies Auxiliary in 1935: “She was shrewd, wise, was possessed of nimble wit, social tact and keen mentality. Flexible in mind, she was equally attuned to profound reasoning and to thoughtful nonsense……..She did not always have to resort to language, for she possessed a feminine sauciness which, invariably held in check, would on occasion evanescently peek through her dignity, carry her message and incidentally add to her charm. An almost inaudible ‘Eh?’ with rising inflection, the flicker of hardly more than an eyelash, a sudden and slightest cock of her head, or the mere beginning of a quizzical and unfinished smile, and she had said much, though without a word.” And Rollins continued “The greatest achievement of Mrs. McCosh was her care of the ill and injured students. Visualize, if you will, the Princeton of her time – no college infirmary, no town hospital, no local trained nurses, and no medical supervision or treatment by the college authorities.” (Selden, 1991).

Mrs. McCosh continued to provide healthcare for the students even after the end of her husband’s administration. She was described as “The saintly Isabella Guthrie McCosh, who, long after her husband’s death, was the angel to many a Princeton lad in illness and distress. (McWilliams, 1923)

The healthcare needs during the 20 years period of Dr. McCosh’s administration included everything from colds to epidemics. For the most serious cases, specialists were engaged to bring resources beyond what Isabella could provide. The most serious health incident occurred in the spring of 1880. Thirty-eight cases of “malarial and typhoid” fever occurred. Seven students died during this catastrophe. The main cause of the outbreak was “the defective state of the college drainage……unhealthy water in boarding houses, and to defective sewage arrangements”. (Selden, 1991) Then again, two years after Dr. McCosh’s retirement, in late spring of 1890, seven students contracted typhoid fever, but there were no deaths in this outbreak. The responses to these extreme situations were to contain the spread by quarantine, and to make band aid fixes to the causes. The band aid fixes included upgrading the latrines, fixing leaky sewage pipes and testing water. It took three years before an adequate water supply was made available to the College and town of Princeton by the Princeton Water Company, which had been established in 1872. These serious incidents emphasized the need for the college to address providing a healthcare system and infrastructure. James and Isabella McCosh campaigned for this cause. It would not be until 1891 that an official system and infrastructure would be realized. (Selden, 1991)

Social Activities

The McCoshes frequently entertained individuals and groups of people from within and outside of the College. These events were often reported in The Daily Princetonian, Nassau Literary Magazine or Town Topics. Here is one such report: “Dr. and Mrs. McCosh have always extended a most cordial hospitality to parents of the students and visitors in town. Their house has been freely open to friends of the college, and they have been easily accessible to the undergraduates for advice in personal matters. The more advanced students have had access to the Doctor’s large and valuable library for consultation, and his informal library meetings have been a source of the greatest enjoyment to the upper classes. We cannot speak too highly of the part Mrs. McCosh has had in the success of her husband’s administration. She has endeared herself to all the students by her kindness and thoughtful goodness, and those who have had the occasion to meet her socially or personally have found her a woman commanding the highest respect and admiration. In cases of sickness she has shown an interest and motherly tenderness to the students, which they can never forget. The college at large unite with the Faculty in acknowledging the debt of gratitude they owe to Mrs. McCosh and expressing their full appreciation of her services.” (W., 1888)

A description of a McCosh reception from The Princetonian follows “On Monday evening, Dr. and Mrs. McCosh held the first reception which they have given in their new house. The reception was tendered especially to the Doctor's class in Metaphysics, and besides these, many Post-Graduates and members of the faculty were present. A large number of ladies from Princeton and the cities also graced the occasion. The chief feature of the evening was the reading of a paper on Robert Elsmere, Mrs. Humphrey Ward's famous novel……….After the paper, social enjoyment was the order. Mrs. McCosh was, as usual, a delightful hostess, and all who were present will remember the evening with pleasure.” (Dr. McCosh's Reception, 1888)

The McCoshes annually entertained each of the undergraduate classes in turn. “On these occasions McCosh survived while Isabella shone. The President yielded to his wife on all matters of social arrangements and decorum. He would greet the students at the door saying, ‘Glad to see you, Sir, hope your well, Sir. there’s Mrs. McCosh.’ The McCoshes provided lavishly for their guests, and Mrs. McCosh kept busy at the entertainments by making sure that everyone had his fill to eat.” (Hoeveler, 2014)

The reception for the senior class of 1879 was reported in the Princetonian as: “On Thursday evening last, Dr. and Mrs. McCosh gave a most enjoyable reception, at their new residence, to the members of the Senior class. The class turned out almost to a man, and were met with that hearty welcome for which our honored President and his wife are noted. The Princeton fair, assisted by some ladies from out of town, did their best to make the occasion pass off as pleasantly as possible. The beauty of the new mansion was the universal topic of conversation. Its elegant rooms have been most tastefully furnished, and it forms a residence every way worthy of the President of the College. The library, especially, was universally admired. With conversation on this and other topics, the time passed rapidly away. The Instrumental Club and a quartet from the Glee Club favored the company with some delightful music, and contributed much to the pleasures of the evening.” (Senior Reception, 1879)

These social events undoubtably had lasting impacts on the students, alumni and institution of the College of New Jersey that lived on in traditions that would become the hallmarks that made Princeton University what it is today. The revival from the disruption and depression of the Civil War, the bonding of classmates together, and the loyalty of alumni were all enhanced. The Alumni Association of Nassau Hall, founded in 1826, would morph into the Princeton Alumni Association of today. The alumni and students who marched to the Princeton - Yale baseball game prior to commencement in 1888 would morph into Princeton University’s annual P-rade.

Legacy

James McCosh said Isabella Guthrie McCosh “…. had a good deal of the Guthrie character. She was characteristically firm, and did not always yield to me” (Fox, 1974). She evidently had her own mind and added to the discussions that she would have been a part of at her dinners, receptions and involvement with students. One illustration of that is “A story is told of the Scot-American philanthropist Andrew Carnegie's first visit to the college when, being met at the railway station by President and Mrs. McCosh, he opened the conversation by stating: ‘Doctor McCosh, for a long time I've been much interested in Princeton.’ Mrs McCosh instantly retorted: ‘Indeed, Mr. Carnegie, thus far we have seen no financial evidences of it.’ As the startled philanthropist admitted afterward, it was a fair retort because it was ‘Scot against Scot.’” (Fox, 1974). James McCosh’s will left his large library of books to the College of New Jersey, with the provision that they were to remain with his wife for her use until she passed. This implies Isabella had the intellectual powers to appreciate these books. One of the books in that library was the Life of George Washington, authored by Woodrow Wilson ’79, and in which Wilson had written an inscription to Isabella.

Fate had put this unlikely girl from Brechin, Scotland in the midst of discussions that advanced the modernization and enlightenment of the world. Growing up in the home of a prominent physician and surgeon exposed her to the era where Victorian medicine was struggling with maladies like cholera that intensified as the age of industrialization bloomed, and tools like the stethoscope and microscope were coming into broader use, and surgery was being revolutionized by anesthesia and soon thereafter by the germ theory and sterilization. Her uncle, Dr. Thomas Guthrie, and husband placed her in the inner circle of the era of the Scottish Enlightenment and the Great Disruption in the Church of Scotland. She spent 16 years at the new Queen’s College, Belfast where her husband was Professor of Logic and Metaphysics. There was the ordeal of the crossing of the Atlantic during the hurricane season. The 20 years living in the President’s house during the era when the nation was recovering from the Civil War, the church was struggling with Darwin’s new concepts and psychology and science were undergoing great change. There were many dinners and the entertaining of faculty, students and parents who came from a wide cross section of America’s elite families. The hosting of visitors from around the world who came to learn about the College of New Jersey. The participation in the society of people living in Princeton during her stay there. All these opportunities presented a front row seat on the discussions that helped the world explore new directions. It is reasonable to speculate that Isabelle Guthrie McCosh’s outgoing personality added to these discussions.

McCosh Infirmary

The most prominent legacy of Isabella McCosh that has come down to the present-day Princeton University is the establishment of a formal healthcare system. This legacy is preserved in the bricks and mortar of the infirmary building, which was named in honor of the contributions that Isabella made to the practice of healthcare on campus. She and Dr. McCosh actively campaigned for the establishment of an institution and building, and she was active in raising funds for the project. Thirty thousand dollars were raised for the building and an additional twenty thousand dollars were raised for an endowment. The construction of the infirmary was launched in 1891. The college of trustees decided to name the building the Isabella McCosh Infirmary Isabella first learned of this from trustee George B. Stewart ’76, who was a dinner guest at the McCosh home. Dr. McCosh was delighted. Isabella’s reaction was "Oh, they must not do that," she protested, "I don't want them to call it after me." Dr. McCosh responded "You have nothing to do about it, Isabella they will do as they please." (Leitch, 2015)

Isabella McCosh was an example of the importance of having women involved in the College three decades before women had the right to vote, and a hundred years before Princeton University admitted the first class of women undergraduates. She accomplished this be doing rather than remonstrating. She was involved in the formation of the “Ladies Auxiliary of the Isabella McCosh Infirmary”, which gave women a means to be involved, and continues to function. She hosted the formation meeting of the Present Day Club, which is a women’s organization that continues to play an important role for women in the town of Princeton. She was involved in the Ivy Hall Library, located in Princeton, which provided for the higher education of women in the 1870’s. She was also active in promoting a new gymnasium and art building.

Retirement

McCosh House

James and Isabella McCosh decided that two decades leadership at the College of New Jersey would be the milestone for transitioning to retirement. In preparation for retirement, James and Isabella bought a lot on Prospect Street, just off the edge of campus. They engaged the well known New York architect A. Page Brown to design a home for their retirement. This house is cited as a classic example of colonial revival architecture. The New York Sun stated that the McCosh house was designed "according to his own ideas of comfort and beauty." Professor William Milligan Sloane, wrote "The house which he built for his occupation is commodious and exquisitely located, with a distant view across fertile lowlands towards the seashore." This home was their final home. Isabella would continue living there in retirement after Dr. McCosh’s death November 16, 1894. Isabelle continued living in this house another 15 years until her death, November 12, 1909. The Quadrangle Club, moved into the house in 1911. A new Quadrangle Club was built and the McCosh house was moved and is preserved in Princeton at 387 – 391 Nassau Street. (Coleman, 1978)

Princeton historian, Freddie Fox ’39, dubbed Isabella McCosh the “Queen of the Alma Mater”, and wrote the following description of Isabella McCosh in retirement: “The mental fire never flickered as time passed. Mrs. McCosh increased in years but her visage kept a youthful sparkle and her dignity never permitted itself a trace of dourness. The mental fire of the piquant lass from Scotland never slackened even in a tired body. Buoyant with kindliness, with loving recollections and with the confidence of her religious faith, she finished her course with spirit. For years after her husband's death in 1894, Mrs. McCosh would stroll in front of Nassau Hall and around the campus. On these occasions, she always wore her best bonnet and, as she moved along the pathways, the students would step aside and doff their hats, standing bareheaded and at attention until she passed by. It was a royal progress in miniature. Isabella was Queen of the Alma Mater.” (Fox, 1974)

Isabella McCosh certainly was revered like a queen. On her 90th birthday, 30 April 1907, the undergraduates presented her with a rock crystal vase, filled with American Beauty roses, to express their affection for her. It was said she “took the greatest interest in the welfare of the students, and knew personally every member of the undergraduate body”. On her 92nd birthday the undergraduate body recognized her for being “most intimately interested in the happiness of the students. Many an older graduate can testify to her thoughtfulness and skill in caring for those whose misfortune it was to fall ill when there was no infirmary to which students might be sent…” (Mrs. McCosh Presented with a Gift on Her Ninetieth Birthday, 1907)

In 1909

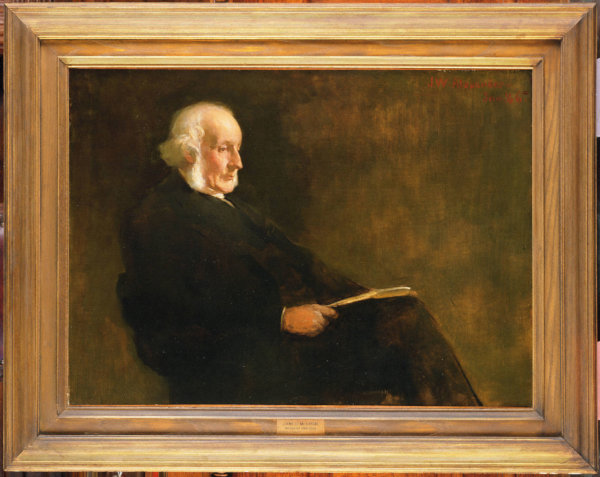

Artist John W. Alexander, class of 1881, and painter of James McCosh’s portrait, contacted the college administration and said he would like to paint Isabella McCosh and donate it to the Isabella McCosh Infirmary. He told how “kind and thoughtful Mrs. McCosh had always been to the students during his four years in College….when in trouble, sickness or distress”. At first Mrs McCosh was firm in her refusal to have the portrait painted and said, “I am such an old woman!” But with explanation about the motivation and intent behind the painting she consented. The painting was completed in a series of sittings in her simple, refined surroundings in the West Room of the retirement Home on Prospect Avenue, which she and President McCosh built. This painting was presented to the University shortly after her 92nd birthday. This painting joined a previous portrait of Isabella, painted by Miss Campbell of New York city in 1892. (Selden, 1991)

Final Chapter

Grave Marker

Isabelle Guthrie McCosh died 12 November 1909 at age 92. Funeral services were conducted at the First Presbyterian Church, by Rev. Sylvester W. Beach. During the day, flags were flown at half-mast. The Princeton University undergraduates formed two lines, one on either side of the path leading from the gate to the President's lot, as was done when President McCosh was interred. A special train arriving at 2 o'clock brought a large number of friends from New York. Following the services, internment was made in the old Princeton Cemetery on Witherspoon Street, beside the graves of President McCosh and her son David McCosh. Revelations 2:19 was written on her grave stone: I KNOW THY WORKS AND CHARITY AND SERVICE AND FAITH AND THY PATIENCE. Thus ended the earthly life of the piquant lass from Brechin, Scotland.

References

Coleman, E. (1978, May 10). The House that McCosh Built. Town Topics, p. 17.

Dr. McCosh's Reception. (1888, December 5). Princetonian, p. 1.

Fox, F. (1974, February 23). The Queen of the Alma Mater. The Daily Princetonian.

Grahan, E. (2018, October 24). Care and Kindness, Along with Spunk: Isabella Guthrie McCosh, Princeton Alumni Weekly.

Hoeveler. (2014). James McCosh and the Scottish Intellectual Tradition. Princeton University Press.

Kerr, A. J. (1942, July 3). We Are Looking Hafer Him. Princeton Alumni Weekly.

Lee, F. B. (Ed.). (n.d.). Genealogical and Persona Memorial of Mercer County, New Jersey (Vols. 2, p. 442).

McWilliams, C. A. (1923, Jan - Jun). Master Surgeons of America: Andrew James McCosh. (M. Franklin, Ed.) Surgery, Gynecology and Obstetrics, p. 884.

Mrs. McCosh Presented with a Gift on Her Ninetieth Birthday. (1907, May 1). Daily Princetonian.

Princetoniana. (n.d.). James McCosh. Retrieved from Princetoniana Museum

Selden, W. K. (1991). A History of the Health Services at Pinceton University. Princeton University press.

Senior Reception. (1879, january 30). Princetonian, p. 8.

W., H. C. (1888, June 1). Dr. McCosh's Administration. Nassau Literary Magazine, p. 85.